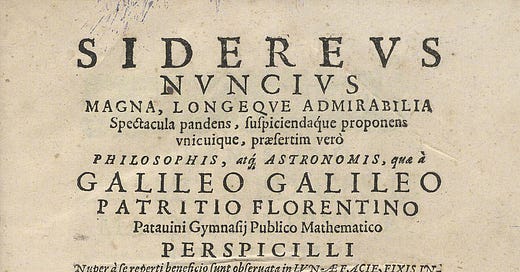

On March 13th, 1610, a previously unknown publisher, Thomas Baglioni, published an unprepossessing 60-page book by a practically unknown 46-year-old mathematician. This book, dedicated to the newly appointed Grand-Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici of Tuscany, turned out to be Galileo Galilei’s first major published work, the Sidereus Nuncius, known in English as either The Sidereal Messenger or The Starry Messenger.

Although Galileo’s lasting contributions to physics would ultimately be in the study of motion, to be discussed on this blog in subsequent posts, the publication of the Nuncius turned out to be a key turning point in the history of Western civilization.

For the purpose of this post, I have relied on a talk in Italian given in 2017 at the Modena open-air festivalfilosofia, entitled Sidereus nuncius di Galileo Galilei, by Paolo Galluzzi, an Italian historian of science and director of the Museo Galileo in Florence since 1982.

The Nuncius, unlike Galileo’s later works, is written in a very dry tone, with no commentary. Galileo wrote that he heard about a telescope, in which it was possible to see images further away that one could with the naked eye, as the images were magnified, and then proceeded to make his own refractive telescope from first principles, combining a convex lens at one end and a concave lens at the other. He then proceeded to point his telescope, with magnifying power of 20, to the heavens, and observed the following:

The Moon has a very uneven surface, with high mountains and low depressions.

When the Moon is not full, the darker part of the disk is an ashen grey, partially lit by light from the Sun reflected on the Earth.

The Milky Way is a region of the sky in which there are huge numbers of stars.

The constellations of Orion and the Pleiades have many more stars than can be seen with the naked eye.

Jupiter is accompanied by 4 satellites [Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto] which revolve around Jupiter.

This small book had an extraordinary, immediate success. According to Galluzzi, there were three reasons:

The book refers to objects and phenomena in the sky that noöne had ever previously seen, nor could they even have imagined them.

The discoveries were made with an instrument, which up to then, few had ever heard of, i.e., the telescope. This instrument was found all over Europe in the previous year, but for the first time, it had been pointed to the heavens.

The discoveries forced a radical change in the received opinions of the populace, and what is taught in the schools and universities.

Within days, despite the incredibly slow means of communication in those times, the news was being discussed by ordinary people in the market places of Europe, and by scientists, theologians, princes and emperors. The English ambassador to Venice, Henry Wotton, wrote to King James I of England about the book. Jörg Füger, ambassador for the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II in Prague, wrote to the beacon of astronomy, Johannes Kepler. Henry IV of France, just before his assassination on May 14, wrote to Galileo asking for some stars to be named in his [Henry’s] honor should Galileo discover any further stars. And so on…

The news also spread to other parts of the world. Very quickly, the news reached Moscow, since one of Galileo’s students was Russian. As for India and China, definitely by 1613 one of the Jesuit colleges in India had heard about the book, and a few months later the Jesuits in Beijing had as well.

Because of the mythology around Galileo, it is sometimes difficult to recognize his actual achievements, which, with respect to the Nuncius, are as follows:

Galileo for a long time had a mechanical machining laboratory in his home, with which he produced instruments such as his military compass, to be sold to his students for supplementary income. There is a shopping list written in Galileo’s hand that shows that Galileo made instruments from his own hands, and did not hand the work over to other artisans. So Galileo would have picked up lead organ pipes and quality crystals in Venice and Murano with which he could create his improved telescopes at home.

Galileo, who had trained as an artist as young man, was able to competently draw the images of the moon, despite the fact that he could only observe through his telescope a fraction of the moon at a time.

Most importantly, Galileo made a mad rush to be the first to publish, and succeeded in this venture.

This last point is crucial. Galileo was by no means the only one to point his telescope to the heavens, and it is not at all clear that he was the first to see, for example, Jupiter’s four satellites. However, Galileo did everything to get published quickly:

He applied for permission to publish from the Venetian authorities before the book was finished, when even the final title had yet to be chosen.

The book was being typeset while he was still making observations.

There are four unnumbered pages in the text, inserted after the fact.

The initial printing had the four satellites named after Cosimo, rather than the Medici family. Some of the initial books therefore had to have the name changed manually.

If we look at the printing of the Nuncius through modern eyes, we can see Galileo acting as the founder of a start-up, doing everything to be the first one to get to the market.

A lot of the initial reception of the Nuncius was skeptical, at times clearly antagonistic. What swung the learned opinion was the Dissertatio cum Nuncio Siderio that Kepler wrote in support of Galileo, who had asked for Kepler’s approval. Despite not seeing Galileo’s discoveries, Kepler was sure that they were real. Because of his stature as the most distinguished astronomer and mathematician in the Empire, Kepler’s praise assured Galileo’s success, but that praise was a double-edged sword. If Galileo had deliberately written about the observations without any commentary, Kepler made the explicit link between these observations and their consistency with the Copernican model, and in so doing alarmed many of Galileo’s enemies in ecclesiastic circles.

Kepler also asked Galileo several embarrassing questions: Why did you not explain how the telescope works? Why did you not cite previous writings on the telescope, including Giovanni Batista della Porta’s 1589 text Magia naturalis or Kepler’s own 1604 text Astronomiae Pars Optica? Why did you not cite any previous authors speculating that the Moon was like the Earth, as did Plutarch and Kepler’s own adviser Michael Maestlin? Finally, why did you not consider the possibility that these new planets are inhabited? This last question was perhaps the most dangerous for Galileo, as it came from a Lutheran.

Kepler’s letter pleased Galileo, as it shut the mouths of his critics, but also alarmed him, as it made him naked. Plus, Kepler, asking for an alliance, in which Galileo would make further observations and Kepler would work on interpreting them, was not received well, as Galileo wanted to be known as a philosopher. Subsequently, Galileo never wrote again to Kepler, nor did he ever send Kepler the telescope that he had promised. Ultimately the latter was able to see through a telescope that Galileo had sent to the Elector of Cologne, who in turn lent it to Kepler.

In summary, the publication of the Nuncius in 1610 made Galileo famous across Europe. Nevertheless, his greatest contributions to science are not in astronomy, despite the trials that he was subjected to for supporting the Copernican system that ultimately placed him in house arrest. It is his work studying motion that is most important. I will be looking at this work in the coming posts.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.