William Gilbert Examines Iron, Calls Aristotle's Earth Element Dead

William Gilbert's De Magnete, Book One, part 2

This post is part of a series of posts about William Gilbert’s De Magnete (On the Magnet1), which is composed of six books. This is the second post on Book One. Here are the previous posts related to De Magnete.

In Book One, William Gilbert writes substantially about the nature of iron. It is important to understand that Gilbert was writing in 1600, some sixty years before Robert Boyle (1627-1691), considered to be the first chemist, published The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes (1661). This means that the language that Gilbert is using is not chemical, but alchemical, language that I am not at all familiar with. Nevertheless, I think his conclusions are fascinating, as they, as we will see, make a significant contribution to the dismantling of the Aristotelian edifice, in which the element earth is deemed to be dead, cold and dry.

In order to understand Gilbert’s discussion, it is necessary to have some (very) basic ideas about alchemy. To simplify my introduction, I will capitalize all alchemical concepts. Therefore, if I write ‘Earth’, that should be understood as the Element called Earth; and if I write ‘earth’, that should be understood as Terra, the earth we live on. This practice will only be for my own writing; when quoting Gilbert, I will simply follow the text.

In alchemy2, there are four Elements, the same ones mentioned by Empedocles (494-434 BCE) and Aristotle: Fire, Air, Water and Earth. Each of the Elements has two of the following four Qualities: Hot, Cold, Dry, Moist. Finally, each Element makes a bodily fluid called a Humor. Here, for example, is one summary of the four Elements, used for centuries in medicine:

Earth, which is Cold and Dry, creates Black Bile;

Air, which is Hot and Moist, creates Red Blood;

Fire, which is Hot and Dry, creates Yellow Bile;

Water, which is Cold and Moist, creates Clear Phlegm.

In addition, there are three Principles, each corresponding to the mixture of two Elements:

Sulfur = Fire + Air;

Mercury = Air + Water;

Salt = Water + Earth.

As alchemy developed, the simple scheme presented above evolved, and I understand that more Humors were invented as needed.

Gilbert begins his presentation of iron as follows, and in so doing, includes some alchemical concepts:

Iron is, by all, classed among metals; it is of bluish color, very hard, grows red hot before fusion [melting], is very hard to fuse, spreads under the hammer, and is resonant. Chemists say that, if fixed earthy sulphur be combined with fixed earthy mercury and these two bodies present not a pure white but a bluish-white color, if the sulphur prevail, iron results. For those hard masters of the metals, who in many various processes put them to the torture, by crushing, calcining, smelting, subliming, precipitating, distinguish this, on account both of the earthy sulphur and the earthy mercury, as more truly the child of earth than any other metal; for neither gold, not silver, nor lead, nor tin, nor even copper do they hold to be so earthy; and therefore it is treated only in the hottest furnaces with the help of bellows; and when thus smelted if it becomes hard again it cannot be smelted once more without great labor; and its slag can be fused only with the utmost difficulty. It is the hardest of metals, subduing and breaking them all, because of the strong concretion of the more earthy substance. [p.34]

Nevertheless, although Gilbert uses the language of alchemy for his discussion, he expresses a lot of skepticism, first examining some comments by chemists:

Aristotle supposes their matter to be an exhalation. The chemists in chorus (unison) declare that sulphur and quicksilver are the prime elements. Gilgil, the Mauretanian, holds the prime element to be ash moistened with water; Georgius Agricola, a mixture of water with earth; and his opinion differs nought from Gilgil's thesis. [p.34]

But this skepticism turns immediately into criticism, with him arguing that the concepts of alchemy hold no meaning for him:

But our opinion is that metals have their origin and do effloresce in the uppermost parts of the globe, each distinct by its form, as do many other minerals and all the bodies around us. The globe of the earth is not made of ash or inert dust. Nor is fresh water an element, but only a less complex consistence of the earth's evaporated fluids. Unctuous bodies (pinguia corpora), fresh water void of properties, quicksilver [mercury], sulphur: these are not the principles of the metals: they are results of another natural process; nor have they a place now or have they had ever in the process of producing metals. The earth gives forth sundry humors, not produced from water nor from dry earth, nor from mixtures of these, but from the matter of the earth itself: these are not distinguished by opposite qualities or substances. Nor is the earth a simple substance, as the Peripatetics imagine. The humors come from sublimed vapors that have their origin in the bowels of the earth. And all waters are extractions from the earth and exudations, as it were. [pp.34-35, emphasis mine]

Instead, Gilbert puts forward a new concept, namely that the fundamental earth substance is closely related to iron, and that the magnetic properties of the earth come from this fundamental earth substance. Furthermore, iron should be considered more pure than gold itself. For me, even if Gilbert still retains some of the vocabulary of alchemy, he is clearly rejecting its principles.

What the chemists (as Geber and others) call the fixed earthy sulphur in iron, is nothing else but the homogenic matter of the globe held together by its own humor, hardened by a second humor: with a minute quantity of earth-substance not lacking humor is introduced the metallic humor. Hence it is said very incorrectly that in gold is pure earth, in iron impure; as though natural earth and the globe itself were become in some sense incomprehensible sense impure. In iron, especially in best iron, is earth in its true and genuine nature. [p.38]

Gilbert adds that not only is iron more pure than gold, but it is far more abundant and useful for humans. In so doing, he is completely ridiculing the alchemists. Furthermore, he hints that the “primordial homogenic telluric [earthly] body” is both the source of magnetism and closely related to iron:

For iron is foremost among metals and supplies many human needs, and they the most pressing: it is also far more abundant in the earth than the other metals, and it is predominant. Therefore it is a vain imagination of chemists to deem that nature's purpose is to change all metals to gold, that being brightest, heaviest, strongest, as though she were invulnerable, would change all stones into diamonds because the diamond surpasses them all in brilliancy and in hardness. Iron ore, therefore, as also manufactured iron, is a metal slightly different from the primordial homogenic telluric body because of the metallic humor it has imbibed; yet not so different but that in proportion as it is purified it takes in more and more of the magnetic virtues, and associates itself with that prepotent form and duly obeys the same. [pp.42-43]

After discussing the nature of iron, Gilbert moves on to where it is found:

The earliest mines were iron mines, not mines of gold, silver, copper or lead: for iron is more sought after for the needs of man; besides, iron mines are plainly visible in every country, in every soil, and they are less deep and less encompassed with difficulties than other mines. […] Furthermore, all those earths when prepared, are attracted by the magnet like iron. Lasting and plentiful is the earth's product of iron. [p.44]

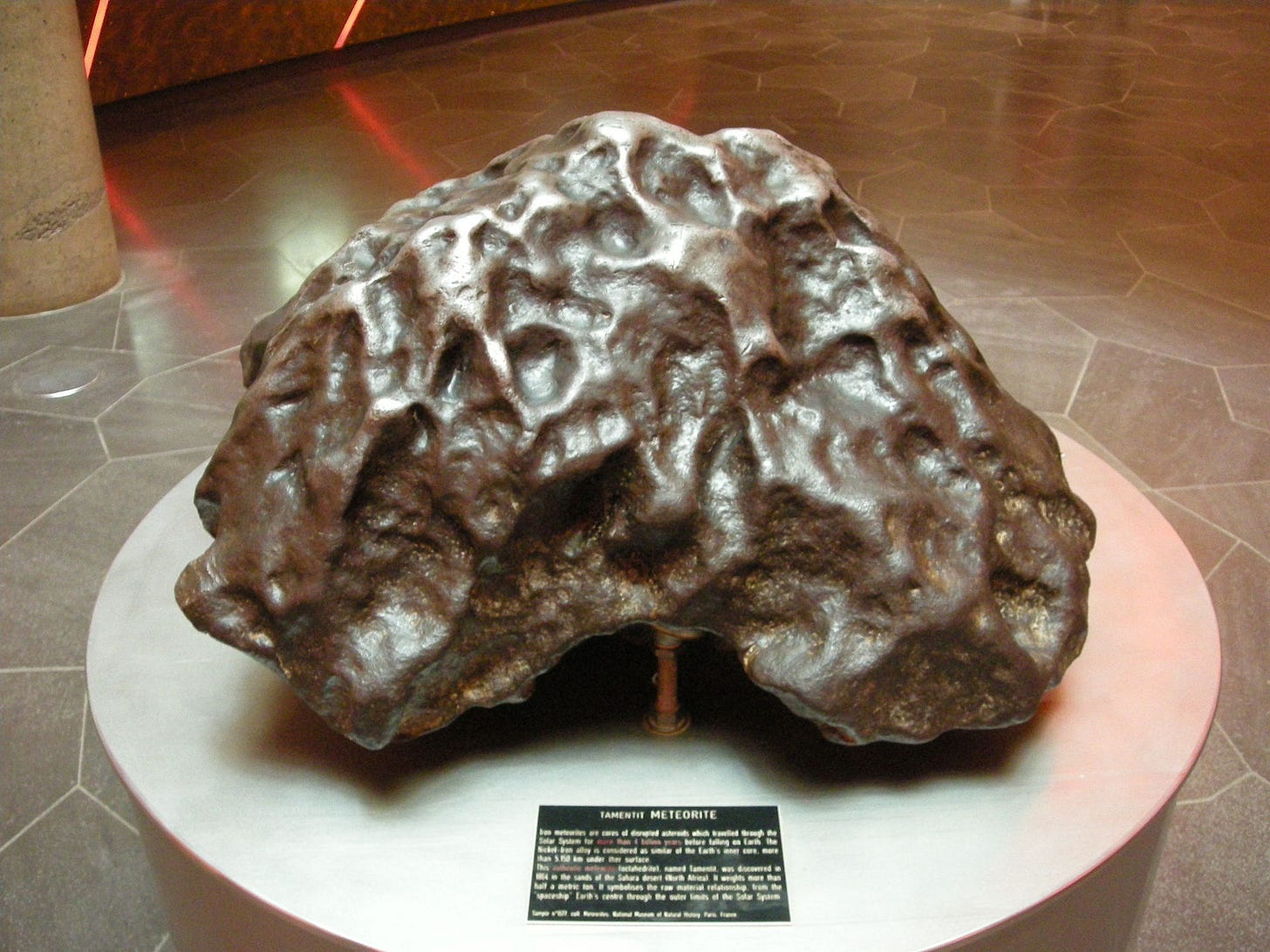

He even mentions that sometimes iron comes from the sky!

But iron is produced not only in the common mother (the globe of Earth), but sometimes is also in the air, in the uppermost clouds from the earth's vapors. [p.45]

Gilbert then moves on to discussing the magnetic properties of iron. Iron ores of certain colours are attracted to each other, but not as strongly as to loadstones. However, after roasting over slow fire, they are much better attracted:

Take some pieces of such ores and roast or rather heat them in a moderate fire so that they many not suddenly split or fly to pieces, and retain them ten or twelve hours in the fire, which is to be kept up and moderately increased; then suffer them to cool...: these stones so manipulated, the loadstone now attracts; they show mutual sympathy, and, when arranged according to artificial conditions, they come together through the action of their own forces. [p.47]

A piece of iron ore has poles, even though most do not know this. When heated in a forge, the strength increases:

But of less perfect ores which, however, under the guise of stone or earth contain a good deal of iron, few possess the power of movement; yet when treated artificially with fire, as told in the foregoing chapter, these acquire polar activity, strength (verticity, as we call it); and not only such ores as miners seek, but even earths simply impregnated with ferruginous matter, and many kinds of rock, do in like manner (provided they be skilfully placed), tend and glide toward those positions of the heavens, or rather of the earth, until they reach the point they are seeking: there they eagerly rest. [p.48]

Wrought iron, i.e., iron in the form of bars after passing through two forges, itself attracts other iron, even if no loadstone has been seen:

But we, steadily trying all sorts of experiments, have discovered that mere iron itself, magnetized by no loadstone, nor impregnated with any extraneous force, attracts other iron, though it does not seize the other iron as eagerly nor as suddenly pulls it to itself as would a strong loadstone. [p.49]

As for a long piece of iron, even if not magnetized, if it is allowed to spin freely, from a thread or in a boat on water, it will align north and south:

All good and perfect iron, if it be drawn out long, acts like a loadstone or like iron rubbed with loadstone: it takes the direction north and south — a thing not at all understood by our great philosophers who have labored in vain to demonstrate the properties of the loadstone and the causes of the friendship of iron for the loadstone. [p.50]

And should there be magnetic variation, a piece of iron and a loadstone will have the same variation:

And it is well to know and to hold fast in memory, that as a strong loadstone and iron magnetized by the same, point not always to toward the true pole, but exactly to the point of variation; likewise will a weaker loadstone and iron that directs itself by its own force, and not by force derived from the impress of any magnet; so too, all iron ores, and all substances imbued with any ferric matter and duly prepared, turn to the same point in the horizon — to the place of variation of the locality concerned (if variation there exist), and there they remain and rest. [p.51]

As for a long piece of iron, it will develop poles:

Iron takes a direction toward north and south, but not with the same point directed toward either pole; for one end of a piece of iron ore or of an iron wire steadily and constantly points to the north and the other to the south, whether it be suspended in air, or floating in water, and whether the specimens be iron bars or thin wires. [p.51]

And should that long piece of iron be cut in two, each half will itself have two poles:

And if you cut off a part, if the farther end of that piece is boreal (northern), the farther end of the other piece, with which it was before joined, will be austral (southern). [p.52]

As for a round piece of iron, it is less likely to form poles:

But, herein, manufactured iron so differs from loadstone and iron ore, that in a ball of iron of whatever size... polarity (verticity) is less easily acquired and less readily manifested than in the loadstone itself, in ore, and in a round loadstone; but in iron instruments of any length the force is at once seen. [p.52]

After discussing these properties of iron, Gilbert examines the use of loadstones for medicine. He accepts the possibility that there might be some benefit, but insists that were that be the case, it would be from a loadstone as loadstone, not as ground-up powder:

[B]ut a loadstone attracts when it is whole, not when reduced to powder, deformed, buried in a plaster; for it does not with its matter attract in such case. [p.54]

Nevertheless, his conclusion is that most claims of the use of loadstone for medical purposes are simply quackery [According to Wiktionary, a sciolist is a person who exhibits only superficial knowledge; a self-proclaimed expert with little real understanding]:

And thus do sciolists wrangle with one another, and confuse the minds of learners with their questionable cogitations, and debate over the question of goat's wool, philosophizing about properties illogically inferred and accepted: but these things will appear more plainly when we come to treat of causes, the murky cloud being dispersed that has so long involved all philosophy. [p.58]

Finally, here are the conclusions of Book One. First, loadstone is a kind of iron ore:

That loadstone and iron ore are the same, and that iron is obtained from both, like other metals from their ores; and that all magnetic properties exist, though weaker, both in smelted iron and in iron ore. [p.59]

More specifically, loadstone is a higher-quality iron ore, used to produce better quality iron:

So, according to our reasoning, loadstone is chiefly earthy; next after it comes iron ore or weak loadstone; and thus loadstone is by origin and nature ferruginous, and iron magnetic, and the two are one in species. Iron ore in the furnace yields iron; loadstone in the furnace yields iron also, but of far finer quality, which is called steel; and the better sort of iron ore is weak loadstone, just as the best loadstone is the most excellent iron ore in which we will show that grand and noble primary properties inhere. It is only in weaker loadstone, or iron ore, that these properties are obscure, or faint, or scarcely perceptible to the senses. [p.63]

Second, the Aristotelian element Earth simply does not exist, and the idea of the four elements of Fire, Air, Water and Earth, is simply wrong:

So we do only see portions of the earth's circumference, of its prominences; and everywhere these are either loamy, or argillaceous, or sandy; or consist of organic soils or marls; or it is all stones and gravel; or we find rock-salt, or ores, or sundry other metallic substances. In the depths of the ocean and other waters are found by mariners, when they take soundings, ledges and great reefs, or bowlders, or sands, or ooze. The Aristotelian element, earth, nowhere is seen, and the Peripateti[c]s are misled by their vain dreams about elements. But the great bulk of the globe beneath the surface and its inmost parts do not consist of such matters; for these things had not been were it not that the surface was in contact with and exposed to the atmosphere, the water, and the radiations and influences of the heavenly bodies; for by the action of these are they generated and made to assume many different forms of things, and to change perpetually. [pp.65-66, emphasis mine]

Third, the loadstone, and all magnetic bodies, act as miniature earths, as they all incorporate matter found in the inner core of the earth:

Yet the loadstone and all magnetic bodies — not only the stone but all magnetic, homogenic matter — seem to contain within themselves the potency of the earth's core and of its inmost viscera, and to have and comprise whatever in the earth's substance is privy and inward: the loadstone possesses the actions peculiar to the globe, of attraction, polarity, revolution, of taking position in the universe according to the law of the whole; it contains the supreme excellencies of the globe and orders them: all this is token and proof of a certain eminent combination and of a most accordant nature. [p.66]

Fourth, since the loadstone acts like the earth, so must the earth act like the loadstone. Therefore, if the loadstone naturally rotates, so does the earth. Gilbert is therefore preparing us for an explanation of the earth’s diurnal rotation, in support of the Copernican system:

But the true earth-matter we hold to be a solid body homogeneous with the globe, firmly coherent, endowed with a primordial and (as in the other globes of the universe) an energic form. By being so fashioned, the earth has a fixed verticity, and necessarily revolves with an innate whirling motion: this motion the loadstone alone of all the bodies around us possesses genuine and true, less spoilt by outside interferences, less marred than in other bodies, — as though the motion were an homogeneous part taken from the very essence of our globe. [pp.68-69]

Gilbert concludes Book One with a final jab at the Aristotelian element Earth, arguing that it is cold and lifeless, and in no way resembles the magnetic homogenic telluric substance that makes up the core of the earth:

Such, then, we consider the earth to be in its interior parts; it possesses a magnetic homogenic nature. On this more perfect material (foundation) the whole world of things terrestrial, which, when we search diligently, manifests itself to us everywhere, in all the magnetic metals and iron ores and marls, and multitudinous earths and stones; but Aristotle’s “simple element,” and that most vain terrestrial phantasm of the Peripatetics, — formless, inert, cold, dry, simple matter, the substratum of all things, having no activity, — never appeared to any one even in dreams, and if it did appear would be of no effect in nature. Our philosophers dreamt only of an inert and simple matter. [p.69]

And what Gilbert wrote about the earth also applies to every fragment thereof, as will be shown in the experiments presented in the following books of De Magnete.

Thus every separate fragment of the earth exhibits in indubitable experiments the whole impetus of magnetic matter; in its various movements it follows the terrestrial globe and the common principle of motion. [p.71]

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

W. Gilbert. De Magnete. Dover, New York, 1958. Translation by P. Fleury Mottelay of De Magnete, first published in 1600.

For an introduction to some basic concepts, I used the three following sites:

When alchemists talk about the "element earth" I don't think they mean a physical substance. For example alchemists associate cold, the planet Saturn, and feminine with earth. From https://www.learnreligions.com/elemental-symbols-4122788

Interesting that Gilbert claims magnetism as a cause of the earth's rotation. Gilbert writes that lodestones spin until their north pole points to the earth's south pole. Why does the earth as a giant lodestone rotate instead of align its pole in a certain direction?