An Infinite Sphere Whose Centre is Everywhere and Circumference is Nowhere

In his De Docta Ignorantia [On Learned Ignorance1], Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464) wrote:

Hence, the world-machine will have its center everywhere and its circumference nowhere, so to speak; for God, who is everywhere and nowhere, is its circumference and center. [Book II, Chapter 12, paragraph 162, p.93, emphasis mine]

In this post, I will discuss this and related sentences from other authors through the centuries. Examining Cusa’s sentence, which gives the impression that he believed the universe to be infinite, has led me through an interesting search, which began while I was preparing my post Johannes Kepler Views an Infinite Universe with Horror. I will address the issue of whether Cusa actually believed the universe to be infinite in my next post.

I found in the endnotes for Kepler’s De Stella Nova2 [On the New Star] and Epitomes Astronomiae Copernicae3 [Epitome of Copernican Astronomy] made by Max Caspar (1880-1956), the main editor of the complete works of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), references to a book by Dietrich Mahnke (1884-1939) entitled Unendliche Sphäre und Allmittelpunkt. Beiträge zur Genealogie der mathematischen Mystik4 [Infinite Sphere and Centre of the Universe. Contributions to the Genealogy of Mathematical Mysticism]. This book is also referred to by Alexandre Koyré (1892-1964) in his From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe5 and by E.J. Aiton (1920-) in his notes to the English-language translation of Kepler’s Mysterium Cosmographicum6.

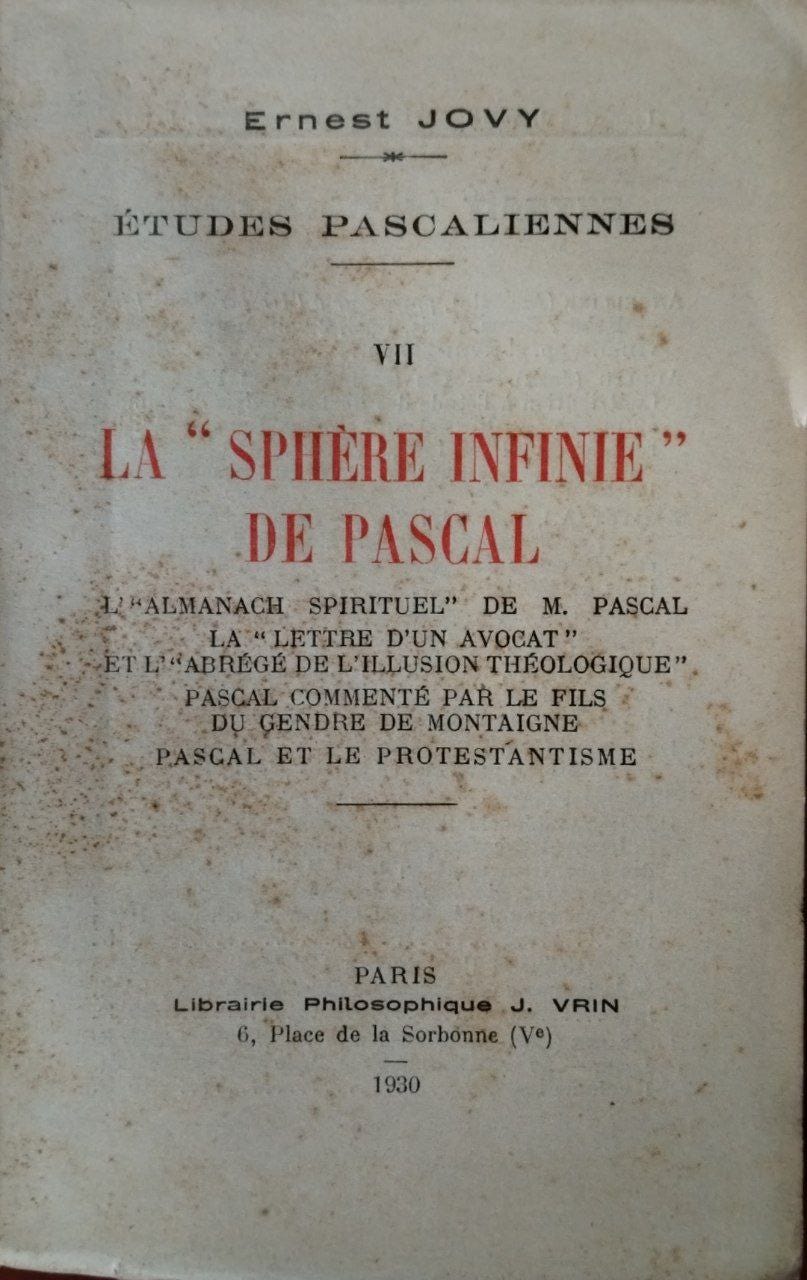

In Mahnke’s book, there is a reference to a book by Ernest Jovy (1859-1933) entitled La “Sphère infinie” de Pascal7 [Pascal’s “Infinite Sphere”], published in 1930 by Librairie philosophique J. Vrin in Paris. I was able to find a copy, many of whose pages are still uncut, from Antiquariat & Kunsthandlung Hieronymus, a bookstore in Munich.

It turns out that phrases similar to “its center everywhere and its circumference nowhere” were used by numerous authors starting in the 12th century. Jovy’s book begins with a quote from Blaise Pascal’s (1623-1662) Pensées8 [Thoughts]:

The whole of the visible world … is an infinite sphere whose centre is everywhere and its circumference nowhere. [emphasis mine]

Jovy then explains that “this comparison with a sphere had been variously applied to God, to the world, to nature, to the universe, which, for the often pantheist ancients, were one and the same.” This reference to a sphere goes back at least to Xenophanes (560 BCE - 478 BCE), then Parmenides (late 6th or early 5th century BCE), Empedocles (494 BCE - 434 BCE) and Plato (427 BCE - 348 BCE).

In the medieval period, the expression “its center everywhere and its circumference nowhere” first appears in the late 12th century, under the pen of Alain de Lille (Alanus de Insulis, 1128-1203).

Deus est sphaera intelligibilis, cujus centrum ubique, circumferentia nusquam. [Jovy, p.21]

Here is the translation into English. All translations from Jovy’s book, whether from the Latin or the French, are my own.

God is an intelligible sphere whose centre is everywhere and circumference is nowhere. [emphasis mine]

According to Vincent de Beauvais (1190-1264), Empedocles had defined God as above:

Empedocles quoque sic Deum diffinire fertur: Deus est sphaera cujus centrum ubique, circumferentia nusquam. [Jovy, p.22]

Here is the translation into English.

It is also stated that Empedocles defined God in this manner: God is a sphere whose centre is everywhere and circumference nowhere. [emphasis mine]

There is another tradition that this phrase actually comes from Hermes Trismegestus, the legendary Hellenistic period figure—according to Wikipedia—that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, and who supposedly wrote a book entitled Hermetica, the basis for a variety of philosophical systems collectively known as Hermeticism.

This idea was promoted by Matthias Baumgartner, who stated in his 1896 book Die Philosophie des Alanus de Insulis9 [The Philosophy of Alain de Lille], that Alain de Lille and Saint Bonaventure would have drawn the above formula from this Hermetic source. But Jovy does not seem convinced, and even refers to a text published in 1859 by Albert Dupuis, Alain de Lille, Etudes de philosophie scolastique10, in which it is revealed that a certain Alain—probably Alain de Lille—was given the nickname Hermes Trismegestus, just to add to the confusion.

Whether the phrase comes from Empedocles or from the Hermetic tradition, it is fascinating to read the transformation that takes place through the centuries. Below, we look at three quotes, with further context. Here is Alain de Lille (12th century):

O what a great difference between the corporeal sphere and the intellectual sphere! In the corporeal sphere, the centre, because of its smallness, is barely to be found anywhere, and the circumference is held to be in many places. But in the intellectual sphere, the centre is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. The centre is a being [créature], since, as time compared to eternity is considered to be just an instant, so a being compared to the immensity of God is naught but a point, or centre. The immensity of God is called the circumference, since by arranging everything in a given manner, he can envelop everything and enclose everything in his immensity. [Jovy, p.22, emphasis mine]

Here is Nicholas of Cusa (15th century):

The ancients did not attain unto the points already made, for they lacked learned ignorance. It has already become evident to us that the earth is indeed moved, even though we do not perceive this to be the case. For we apprehend motion only through a certain comparison with something fixed. For example, if someone did not know that a body of water was flowing and did not see the shore while he was on a ship in the middle of the water, how would he recognize that the ship was being moved? And because of the fact that it would always seem to each person (whether he were on the earth, the sun, or another star) that he was at the “immovable” center, so to speak, and that all other things were moved: assuredly, it would always be the case that if he were on the sun, he would fix a set of poles in relation to himself; if on the earth, another set; on the moon, another; on Mars, another; and so on. Hence, the world-machine will have its center everywhere and its circumference nowhere, so to speak; for God, who is everywhere and nowhere, is its circumference and center. [Book II, Chapter 12, paragraph 162, pp.92-93, emphasis mine]

Finally, here is Blaise Pascal (17th century):

So let us contemplate the whole of nature in its full and mighty majesty, let us disregard the humble objects around us, let us look at this scintillating light, placed like an eternal lamp to illuminate the universe. Let the earth appear a pinpoint to us beside the vast arc this star describes, and let us be dumbfounded that this vast arc is itself only a delicate pinpoint in comparison with the arc encompassed by the stars tracing circles in the firmament. But if our vision stops there, let our imagination travel further afield. Our imagination will grow weary of conceiving before nature of producing. The whole of the visible world is merely an imperceptible speck in nature's ample bosom, no idea comes near to it. It is pointless trying to inflate our ideas beyond imaginable spaces, we generate only atoms at the cost of the reality of things. It is an infinite sphere whose centre is everywhere and its circumference nowhere. In the end it is the greatest perceivable sign of God's overwhelming power that our imagination loses itself in this thought. [paragraph 230, p.66, emphasis mine]

We can see from the above that although all three writers refer to God, the focus changes through the centuries. Alain de Lille focuses solely on the intellectual space, Pascal on the immensity, even the infinity, of space, while Cusa is somewhere in the middle.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

Jasper Hopkins. Nicholas of Cusa on Learned Ignorance. A Translation and an Appraisal of De Docta Ignorantia. Minneapolis: The Arthur J. Banning Press. 2nd ed., online. 1985.

Johannes Kepler. De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii, et ejus exortum de novo iniit, Trigono Egneo (1606). In Johannes Kepler, Gesammelte Werke, Band I, pp.149-487. Herausgegeben von Max Caspar. München: C.H.Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1938. p.422, note 23.14.

Johannes Kepler. Epitome Astronomiae Copernicae (1618-1621). In Johannes Kepler, Gesammelte Werke, Band VII, pp.7-537. Herausgegeben von Max Caspar. München: C.H.Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1991. p.576, note 45.10.

Dietrich Mahnke. Unendliche Sphäre und Allmittelpunkt. Beiträge zur Genealogie der mathematischen Mystik. Haale/Saale: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1937. p.43.

Alexandre Koyré. From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1957. p.279, note 19.

Johannes Kepler. Mysterium Cosmographicum: The Secret of the Universe. Translation by A.M. Duncan. Introduction and Commentary by E.J. Aiton. With a Preface by I. Bernard Cohen. New York: Abaris, 1981. p.231, note 1.

Ernest Jovy. La “Sphère infinie” de Pascal. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1930.

Blaise Pascal. Pensées and Other Writings. Translated by Honor Levi. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Anthony Levy. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Matthias Baumgartner. Die Philosophie des Alanus de Insulis, in Zusammenhange mit den Anschauungen des 12. Jahrhunderts. Münster: Druck und Verlag der aschendorffschen Buchhandlung, 1896. pp.117-118.

Albert Dupuis. Alain de Lille, Etudes de philosophie scolastique. Lille: Imprimerie de L. Damel, 1859.

I was introduced to these concepts while organizing with LaRouche in the 80’s. You might find the following of interest:

“Lyndon LaRouche turned out to be right.”

“May his memory Live Forever.”

Sergey Glasyev

(Sergey Glazyev is a Russian politician and economist, a member of the National Financial Council of the Bank of Russia, and a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He is presently the Commissioner for Integration and Macroeconomics within the Eurasian Economic Commission, the executive body of the Eurasian Economic Union).

In light of Vladimir Putin’s appointment of the economist Andre Belousov as the Minister of Defense and Sergei Shoigu as the Secretary of the Security Council , and given the existential threat of the NATO/collective west’s proxy wars vs the BRICS’, BRI, and the SCO, (whom have adopted the key tenets of the 19th Century “American System of Political Economy”); take heed of Mr. Glazyev’s tribute to the world renowned Economist Lyndon LaRouche on the Centenary of his birth, 20220908.

https://larouchepub.com/pr/2022/20220916_glazyev_praises_larouche_on_centenary.html