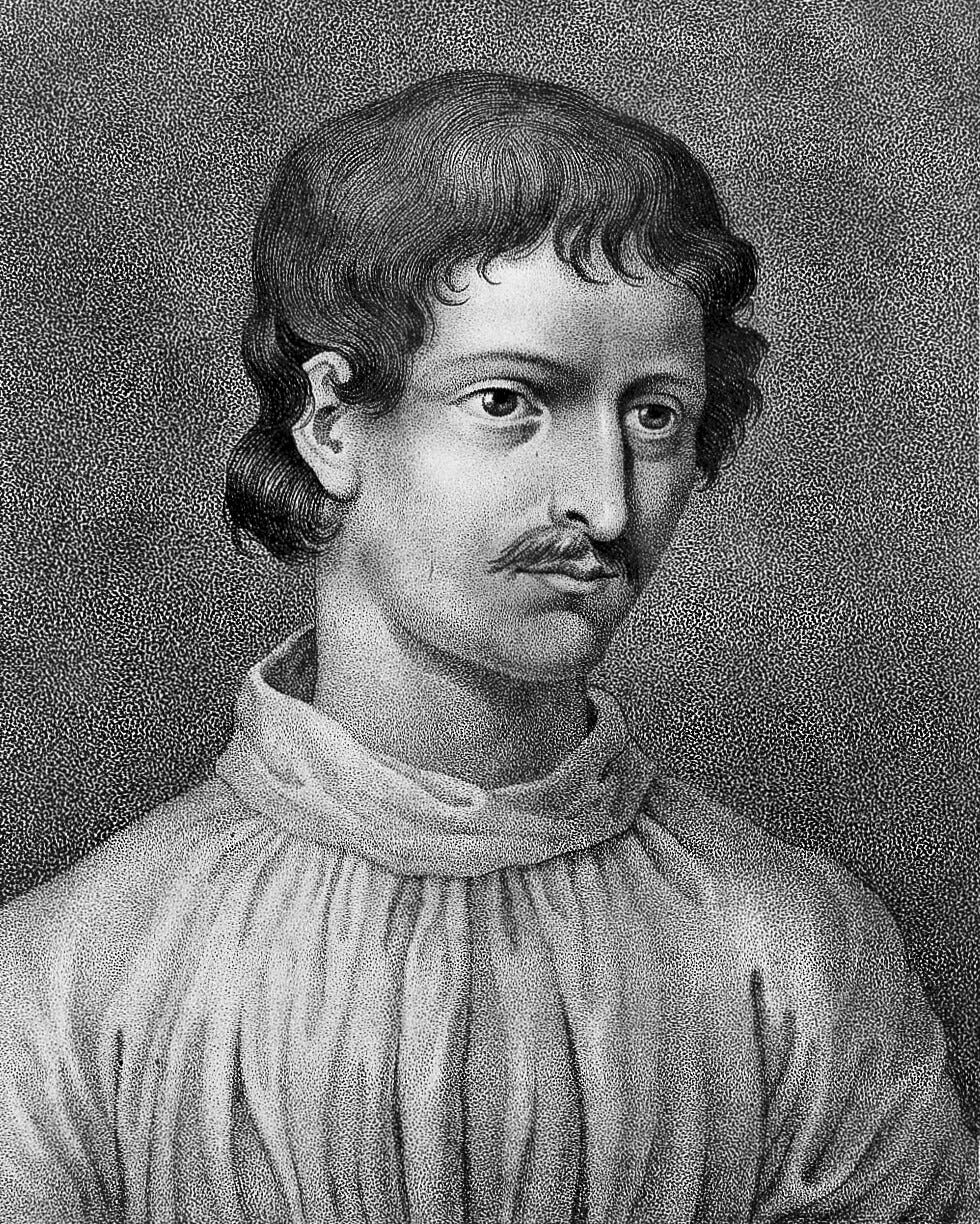

In my previous post, Giordano Bruno the Thinker, I briefly introduced this radical thinker. In this post, I will focus on some of his ideas pertaining to science. This is just one aspect on his very complex thought, which covered a number of subtleties on spirituality and religion, for which he paid the ultimate price. However, we will just stick to science.

The works most relevant to science written by Giordano Bruno are his Italian works from his stay in London (1583-1585) and his Latin works, published in Frankfurt, from his stay in Germany (1588-1592).

While in London, he wrote six Italian works, the first three of which can be said to pertain to science. All of these have been translated into English. Each of these works contains five dialogues.

La cena de le ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper1, 1584)

De la causa, principio, et uno (Cause, Principle, and Unity2, 1584)

De l'infinito universo et mondi (On the Infinite Universe and Worlds3, 1584)

The Latin works are as follows. Each of these is a full dissertation.

De triplici minimo et mensura (On the Threefold Minimum and Measure, 1591)

De monade numero et figura (On the Monad, Number, and Figure, 1591)

De innumerabilibus, immenso, et infigurabili (Of Innumerable Things, Vastness and the Unrepresentable, 1591)

There is no English translation for these Latin works. Carlo Monti published in 1980 an Italian edition, entitled Opere latine di Giordano Bruno.4

In this post, I will focus on the three Italian works mentioned above. In my opinion, Giordano Bruno was the writer who most clearly wrote about the nature of an infinite, static universe.

But before beginning, perhaps we should consider why this topic is important. Simply, the debate is as relevant today as it was in 1600, when Bruno was burnt at the stake for daring to make his claims. Since Rudolph Clausius (1822-1888) and Ludwig Boltzmann (1844-1906), and the development of the concepts of thermodynamics and entropy, the infinite universe has been under attack.

A clear example can be found in Arthur Eddington’s (1882-1944) The Nature of the Physical Universe,5 in which he rants against both infinite space and time:

Space is boundless by re-entrant form not by great extension. That which is is a shell floating in the infinitude of that which is not. We say with Hamlet, “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space’’.

But the nightmare of infinity still arises in regard to time. The world is closed in its space dimensions like a sphere, but it is open at both ends in the time dimension.

I am not sure that I am logical but I cannot feel the difficulty of an infinite future time very seriously. […] It should … be noted that according to the second law of thermodynamics the whole universe will reach thermodynamical equilibrium at a not infinitely remote date in the future. Time’s arrow will then be lost altogether and the whole conception of progress towards a future fades away.

But the difficulty of an infinite past is appalling. It is inconceivable that we are the heirs of an infinite time of preparation; it is not less inconceivable that there was once a moment with no moment preceding it. [p.83, my emphasis]

Arthur Eddington was by no means a nobody. He is credited with “proving” Einstein’s general relativity by travelling to the island of Principe, off the coast of Africa, to observe a solar eclipse that took place on 29 May 1919. (I will write later about this “proof”.) He was also one of the academic advisors of Georges Lemaître (1894-1966), who invented the Big Bang.

In The Ash Wednesday Supper, Theophilus, Bruno’s voicepiece, recounts to friends a dinner that took place at the residence of Sir Fulke Greville, which was attended by the Nolan, as Bruno called himself, since he came from Nola, outside of Naples. In this dinner, the Nolan faces off with two Oxford Aristotelians, Nundinius and Torquatus.

In the First Dialogue, Bruno outlines his support for the ideas of Copernicus:

Theophilus. He was a man of profound, refined, diligent, and mature genius, second to none of the astronomers who preceded him, except in so far as he came later than them in time. His judgment in matters of natural philosophy was far superior to that of Ptolemy, Hipparchus, Eudoxus, and all the others who followed in their footsteps. He got so far because he freed himself from a number of false presuppositions, not to say blindness and error, which characterize the commonly accepted philosophy. [p.29]

However, Bruno states that by staying within the bounds of mathematics, Copernicus did not go far enough:

Yet he did not leave this philosophy far enough behind him; for, in so far as he was a student of mathematics rather than of nature, he was unable to penetrate those depths which would have allowed him to eradicate the useless and inappropriate principles from which it stems. Only by so doing would he have been able to dispel completely the contradictions it contains, free himself and others from many vain speculations, and fix our attention on things which are constant and certain. [p.29]

Nevertheless, the contributions of Copernicus are crucial:

That said, who will ever be able to praise sufficiently the great and noble genius of this German? Heedless of the vulgar herd, he stood firm against the torrent of contrary beliefs; and although almost destitute of direct proofs, he took up the despised and rusty fragments which he found in antiquity until, with that mathematical rather than natural kind of reasoning of his, he had rendered them newly shining, coherent, and sound. Thus he rehabilitated a cause formerly covered with ridicule and scorn until it became once more honoured, valued, generally considered closer to the truth than the theory it replaced, and certainly more convenient and agile for the theory and calculation of the phenomena. [pp.29,31]

The core of the arguments in favor of Copernicus are presented in the Third Dialogue, in which Theophilus is recounting the Nolan facing off against Nundinius. The latter begins by claiming that Copernicus did not believe his own ideas:

Theophilus. “Well then,” he said in Latin, “I will interpret what we were saying for you. We were saying that Copernicus should not be considered as having said that the earth moves; for that is neither proper nor possible. Rather, he attributed movement to it, instead of to the eighth sphere of the heavens, for greater convenience in calculation.” The Nolan said that if this was the only reason which made Copernicus claim that the earth moves, and no other, then he had clearly failed to understand him. But without any doubt, Copernicus meant what he said, and did all he could to prove it. [p.89]

This idea of Nundinius comes from the preface that appears at the beginning of Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus, but Bruno does not buy this idea, as writes Hillary Gatti:

This hypothetical interpretation of Copernicanism had been powerfully supported by the anonymous preface added just before publication to the dying Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. The name of the author of this preface — the Protestant theologian Andreas Osiander — would only be revealed in public by Kepler in 1604. Bruno appears not to have known who wrote it, although he was the first to suggest in print that it was surely not written by Copernicus himself. [p.xxviii]

Nundinius claims that the earth cannot move, as it is the center of the universe. The Nolan dismisses this argument as not even worthy of being called such, and introduces the concept of the infinite universe. Note that Bruno is writing that all interactions between bodies are relative to other bodies; Bruno can thus be considered to be a precursor of Leibniz and Ernst Mach.

Theophilus. Then Nundinius said that it cannot be true that the earth moves, because it is the middle and centre of the universe and has to be considered the fixed and constant foundation of all motion. The Nolan replied that the same thing could be said by those who believe that the sun is in the middle of the universe. They think that the sun is therefore immobile and fixed, as Copernicus and many others have claimed, believing that the universe has a circumference. So that this kind of reasoning (if it can be called reasoning) carries no weight with those who are of a contrary opinion; while at the same time it presupposes its own principles. Above all, it carries no weight with the Nolan, who proposes an infinite universe within which no body can be said to be in the middle, or on the edge, or between one and the other — but only to be in relation to other bodies and boundaries which are specifically defined. [p.115]

In the Fifth Dialogue, Theophilus smashes the crystal spheres of the Ptolemaic system, especially the eighth sphere of the so-called “fixed stars,” which Bruno claims themselves move, but are so distant that their motion is imperceptible:

So the fact that we do not see much movement in those stars, and that they do not appear to move further away from or nearer to each other, does not mean that they do not move in the same way as these. For there is no reason whatever why they should not be subject to the same influences as these are, or why one of those bodies should not circle around another one. So it is not proper to call them fixed because they really keep the same distance between themselves and us, but only because their movement is imperceptible to us. This can be seen by the example of a very distant ship which, even if it moves thirty or forty yards, will nevertheless appear to be still, as if it were not moving at all. In the same way, it is necessary to consider the distance of great and very luminous bodies, many of which may be as large and as bright as the sun or even more so, but whose orbits and movements, despite their magnitude, cannot be perceived. So, if some of those stars move towards each other, we cannot verify it except by means of lengthy observations, which still have to be begun and pursued. For nobody has believed in such movements, searched for them, or presumed them to be possible. And we all know that the beginning of an inquiry depends on the knowledge that such a phenomenon exists, or is at least possible or probable, and the inquiry profitable. [p.169]

According to Bruno, the idea of an infinite space with innumerable worlds was known in ancient times:

Theophilus. Now this arrangement of the bodies in the ethereal region was understood by Heraclitus, Democritus, Epicurus, Pythagoras, Parmenides, and Melissus, as they make clear in those fragments which have survived. From these it is evident that they thought of an infinite space, an infinite region, an infinite extension capable of including infinite and innumerable worlds similar to this one, which move in their respective orbits just as the earth moves in hers. In antiquity these worlds were called ethera, that is runners or couriers: ambassadors heralding the magnificence of the one Almighty with a musical harmony bearing witness to the ordered constitution of nature, the living mirror of the infinite godhead. This name of ethera has since been taken away from them by blind ignorance, and given to certain quintessences, within which these tiny lights or lanterns are thought of as fixed as if by nails. [p.173]

Despite his antagonism for Aristotle, Bruno does seem to retain the idea that there is naught besides local motion:

There is nothing which can be said to be naturally eternal except the substance which is matter, which itself is in a continual state of mutation. [...] I am telling you that the cause of its local motion, both of the whole body and of its component parts, is the need for vicissitude: not only so that everything can be in every place, but also so that by this means everything has all dispositions and forms. For this reason, local motion has very justly been considered the principle of all other motion and form; for without this, there can be no other. Aristotle was able to notice this motion according to the dispositions and qualities of the parts of the earth; but he did not understand that kind of local motion which is the principal one. [p.185]

In the third London text, On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, Philotheo, or Theophilo, Bruno’s voicepiece, directly takes on Aristotelean arguments against the infinite universe, most of which appear in De Caelo (On the Heavens).

In the First Dialogue, Philotheo asks why would anyone want to restrict the majesty of God by having Him create a mere finite universe?

PHIL. We are then at one concerning the incorporeal infinite; but what preventeth the similar acceptability of the good, corporeal and infinite being? And why should not that infinite which is implicit in the utterly simple and individual Prime Origin rather become explicit in his own infinite and boundless image able to contain innumerable worlds, than become explicit within such narrow bounds? So that it appeareth indeed shameful to refuse to credit that this world which seemeth to us so vast may not in the divine regard appear a mere point, even a nullity? [p.257]

Why do you desire that centre of divinity which can (if one may so express it) extend infinitely to an infinite sphere, why do you desire that it should remain grudgingly sterile rather than extend itself, as a father, fecund, ornate and beautiful? Why should you prefer that it should be less or indeed by no means communicated, rather than that it should fulfil the scheme of its glorious power and being? Why should infinite amplitude be frustrated, the possibility of an infinity of worlds be defrauded? Why should be prejudiced the excellency of the divine image which ought rather to glow in an unrestricted mirror, infinite, immense, according to the law of its being? [pp.260-261]

In the Second Dialogue, Philotheo explains that no matter how far we can see into the heavens, there are more worlds, most of which cannot be perceived:

PHIL. I believe and understand that beyond this imagined edge of the heaven there is always a [further] ethereal region with worlds, stars, earths, suns, all perceptible one to another, that is each to those which are: within or near; though owing to the extreme distance they are not perceptible to us. [p.298]

In the Third Dialogue, Elpino asks Philotheo a number of questions, clarifying a number of issues. Philotheo begins:

PHIL. [The whole universe] then is one, the heaven, the immensity of embosoming space, the universal envelope, the ethereal region through which the whole hath course and motion. Innumerable celestial bodies, stars, globes, suns and earths may be sensibly perceived therein by us and an infinite number of them may be inferred by our own reason. The universe, immense and infinite, is the complex of this [vast] space and of all the bodies contained therein. [p.302]

Elpino asks about the epicycles and deferents of Ptolemy:

ELP. Indubitable that the whole fantasy of spheres bearing stars and fires, of the axes, the deferents, the functions of the epicycles, and other such chimeras, is based solely on the belief that this world occupieth as she seemeth to do the very centre of the universe, so that she alone being immobile and fixed, the whole universe revolveth around her.

PHIL. This is precisely what those see who dwell on the moon and on the other stars in this same space, whether they be earths or suns. [p.303]

Elpino asks about the innumerable suns and why we cannot see them all:

ELP. There are then innumerable suns, and an infinite number of earths revolve around those suns, just as the seven we can observe revolve around this sun which is close to us.

PHIL. So it is.

ELP. Why then do we not see the other bright bodies which are earths circling around the bright bodies which are suns? For beyond these we can detect no motion whatever; and why do all other mundane bodies (except those known as comets) appear always in the same order and at the same distance?

PHIL. The reason is that we discern only the largest suns, immense bodies. But we do not discern the earths because, being much smaller, they are invisible to us. [p.304]

Finally, Elpino inquires about the relationship of the matter in the sun and in the earth:

ELP. You believe then that the prime matter of the sun differeth not in consistency and solidity from that of the earth? (For I know that you do not doubt that a single prime matter is the basis of all things.)

PHIL. This indeed is certain; it was understood by Timaeus, and confirmed by Plato. All true philosophers have recognized it, few have explained it, no one in our time hath understood it, so that many have confused understanding in a thousand ways, through corruption of fashion and defect of principles. [pp.306-307]

The Third Dialogue moves on to an acrimonious exchange between a very angry Burchio, who rejects everything that Philotheo has been saying, and Fracastoro, who is trying to explain Burchio that Bruno is correct. When Burchio asks about the “natural order” of Aristotle, Fracastoro calmly explains that it simply does not exist:

FRAC. I would conclude as follows. The famous and received order of the elements and of the heavenly bodies is a dream and vainest fantasy, since it can neither be verified by observation of nature nor proved by reason or argued, nor is it either convenient or possible to conceive that it exist in such fashion. But we know that there is an infinite field, a containing space which doth embrace and interpenetrate the whole. In it is an infinity of bodies similar to our own. No one of these more than another is in the centre of the universe, for the universe is infinite and therefore without centre or limit, though these appertain to each of the worlds within the universe in the way I have explained on other occasions, especially when we demonstrated that there are certain determined definite centres, namely, the suns, fiery bodies around which revolve all planets, earths and waters, even as we see the seven wandering planets take their course around our sun. Similarly we shewed that each of these stars or worlds, spinning around his own centre, hath the appearance of a solid and continuous world which taketh by force all visible things which can become stars and whirleth them around himself as the centre of their universe. Thus there is not merely one world, one earth, one sun, but as many worlds as we see bright lights around us, which are neither more nor less in one heaven, one space, one containing sphere than is this our world in one containing universe, one space or one heaven. [p.322]

In the second London text, Cause, Principle and Unity, Bruno directly presents, defends and develops arguments from Pythagoras, Parmenides and Plato, the latter mostly from the Timaeus.

In the Second Dialogue, in an exchange between Dicsono and Teofilo, the latter, elaborates that all bodies have souls, i.e., are alive.

Dicsono. I seem to be hearing something very novel. Are you claiming, perhaps, that not only the form of the universe, but also all the forms of natural things are souls?

Teofilo. Yes.

Dicsono. But who will agree with you there?

Teofilo. But who could reasonably refute it?

Dicsono. Common sense tells us that not everything is alive.

Teofilo. The most common sense is not the truest sense. [p.42]

Dicsono. So, in short, you hold that there is nothing that does not possess a soul and that has no vital principle?

Teofilo. Yes, exactly. [p.43]

With respect to the ubiquity of the world soul, Teofilo distinguishes between the corporeal and the spiritual, perhaps as a precursor of Descartes:

Please note that if we say the world soul and universal form are everywhere, we do not mean in a corporeal or dimensional sense, for they are not of that nature and cannot be found so in any part. They are everywhere present in their entirety in a spiritual way. [p.49]

In the Third Dialogue, Teofilo elaborates on the Platonic forms, as explained in the Timaeus:

Teofilo. This is what the Nolan holds: there is an intellect that gives being to everything, which the Pythagoreans and the Timaeus call the ‘giver of forms’; a soul and a formal principle which becomes and informs everything, that they call ‘fountain of forms’; there is matter, out of which everything is produced and formed, and which is called by everyone the ‘receptacle of forms’. [p.61]

And, of course, in his inimitable style, Bruno cannot miss making a final jab at Aristotle, as incapable philosopher.

Dicsono. You please me greatly, and I praise you in equal measure, for just as you are not as vulgar as Aristotle, you are neither as pretentious nor offensive as he, devoting himself to belittling the opinions of all other philosophers as well as their manner of philosophizing.

Teofilo. Of all the philosophers, I know none more reliant upon fancies and more remote from nature than he [Aristotle]. Even if he says excellent things at times, it is recognized that they are not derived from his own principles, but are always propositions borrowed from other philosophers, such as those divine things we see in the books On Generation, Meteors and On Animals and Plants. [p.64]

In the Fifth Dialogue, Teofilo gives the most cogent explanation of the One of Parmenides, mocked by Aristotle in the latter’s Physics, that I have ever read. In my opinion, the Parmenides is the Platonic dialogue most difficult to understand. Reading Bruno, all of sudden it makes sense.

Teofilo. The universe is, therefore, one, infinite and immobile. I say that the absolute possibility is one, that the act is one; the form, or soul, is one, the matter, or body, is one, the thing is one, being is one. The maximum, and the optimum, is one: it cannot be comprehended and is therefore indeterminable and not limitable, and hence infinite and limitless, and consequently immobile. It has no local movement since there is nothing outside of it to which it can be moved, given that it is the whole. It does not engender itself because there is no other being that it could anticipate or desire, since it possesses all being. It is not corrupted because there is no other thing into which it could change itself, given that it is everything. It cannot diminish or grow because it is an infinity to or from which nothing can be added or subtracted, since the infinite has no measurable parts. It is not alterable in terms of disposition, since it possesses no outside to which it might be subject and by which it might be affected. Moreover, since it comprehends all contraries in its being in unity and harmony, and since it can have no propensity for another and new being, or even for one manner of being and then for another, it cannot be subject to change according to any quality whatsoever, nor can it admit any contrary or different thing that can alter it, because in it everything is concordant. It is not matter, because it is not configured or configurable, nor it is limited or limitable. It is not form, because it neither informs nor figures anything else, given that it is all, that it is maximum, that it is one, that it is universal. It is neither measurable nor a measure. It does not contain itself, since it is not greater than itself. It is not contained, since it is not less than itself. It is not equal to itself, because it is not one thing and another, but one and the same thing. Being one and the same, it does not have distinct beings; because it does not have distinct beings, it has no distinct parts; because it has no distinct parts, it is not composite. It is limit such that it is not limit, form such that it is not form, matter such that it is not matter, soul such that it is not soul: for it is all indifferently, and hence is one; the universe is one. [p.87]

In today’s world, with the absurdities of the finite universe of theoretical physics, with singularities in space (black holes) and time (Big Bang, Heat Death), we need a new Giordano Bruno to call for a new physics.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

Giordano Bruno. The Ash Wednesday Supper. Translated by Hillary Gatti. University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Giordano Bruno. Cause, Principle and Unity. Translated and edited by Robberto de Lucca. Essays on Magic. Translated and edited by Richard J. Blackwell. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Dorothea Waley Singer. Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thought. With Annotated Translation of His Work On The Infinite Universe and Worlds. New York: Henry Schuman, 1950.

Giordano Bruno. Opere Latine: Il triplice minimo e la misura; La monade, il numero e la figura; L'immenso egli innumerevoli. A cura di Carlo Monti. Unione Tipografico-editrice Torinese, 1980.

Sir Arthur Eddington. The Nature of the Physical World. Ann Arbor Paperbacks, The University of Michigan Press, 1968. First published by Cambridge University Press in 1928.

Today I learned that Giordano Bruno was a spy. He lived in London for two years and pal'ed around with "Father of Science" Sir Bacon's buddies Phillip Sydney and Fulke Greville and worked for Waslingham according to this Yale University Press book. (no recorded meetings with Bacon but there's no doubt it happened). Bacon was 23-25 at the time and in London. Bacon was also a spy. Well everybody was in some sense, but Bacon worked with Walsingham as did his brother his whole life. The espionage of science and the science of espionage.

A professional spy/scientist was at the first meetings of the Royal Society. He's also the first known initiate of Freemasonry. A guy named Sir Robert Moray

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Giordano-Bruno-Embassy-Affair-Yale/dp/0300094515

Curiouser and curiouser. It was a time of nearly unmatched genius. Athens 300 BCish, Rome Oish, Florence 1400ish, London 1600ish.

Wish I had time to read all these posts man! They look great!

I think it was Humboldt who wrote in his Cosmos, that the universe is expanding at the same rate, as the rate we improve and perfect our telescopes.