Pierre de Fermat's Principle of Least Time

I recently came across a book just published by Jason Ross, entitled The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes: A Sourcebook on Pierre de Fermat’s Principle of Least Time1. Therein, Ross presents, in English, the correspondence Pierre de Fermat (1607-1665) undertook with René Descartes (1596-1650) and the latter’s followers. The correspondence was taken from the collected works of Fermat2 and Descartes3 and translated from the French by Ross.

The key question at the time with respect to light was the nature of refraction, i.e., what happens when light passes from one medium into another, as in, for example, from air into water. I have previously written about this problem in the post Christiaan Huygens Explains the Refraction of Light. Therein I wrote:

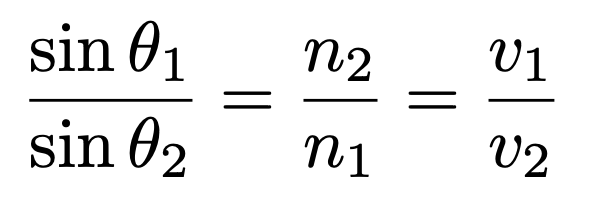

Huygens’s explanation of refraction provides a direct explanation of Snell’s Law, named after Willebrord Snellius [Willebrord Snel van Royen] (1580-1626), although it has been known as early as Ibn Sahl (940-1000): the sines of the angles of incidence and refraction are in inverse relation with the refractive indices of the two media and in direct relation with the speeds of light in the two media. If θ₁ and θ₂ are respectively the angle of incidence and the angle of refraction, n₁ and n₂ are respectively the refractive indices of the two media and v₁ and v₂ are respectively the speeds of light in the two media, then the following holds:

Finally, Huygens concludes that his model supports the position of Pierre de Fermat (1607-1665) over that of René Descartes (1596-1650):

I will finish this theory of refraction by demonstrating a remarkable proposition which depends on it; namely, that a ray of light in order to go from one point to another, when these points are in different media, is refracted in such wise at the plane surface which joins these two media that it employs the least possible time: and exactly the same happens in the case of reflexion against a plane surface. Mr. Fermat was the first to propound this property of refraction, holding with us, and directly counter to the opinion of Mr. Des Cartes, that light passes more slowly through glass and water than through air. [Huygens4 , pp.42-43, my emphasis]

The debates between Fermat and Descartes and the latter’s followers took place decades before 1690, when Huygens published his Traité de la Lumière (Treatise on Light). It is for this reason that Ross’s book is useful, as it provides the background for Huygens’s work.

The initial exchange between Descartes and Fermat took place, with Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) as intermediary, during the period 1637-1638. In his Dioptrique (Dioptrics), Descartes “explained” refraction in a completely far-fetched manner, with transparent cloth between the two media, tennis balls and tennis rackets. Fermat took up the gauntlet and called Descartes out, politely, for writing nonsense.

Some twenty years later, in 1657, an exchange took place betwen Marin Cureau de la Chambre (1594-1669) and Fermat. De la Chambre had completed his Lumière (Light) that year and sent a copy to Fermat; the text would be published in 1662. Therein, de la Chambre proposed that light took the shortest path as it passed through the two media. Fermat’s response was that it was not the shortest path, but the shortest time that counted:

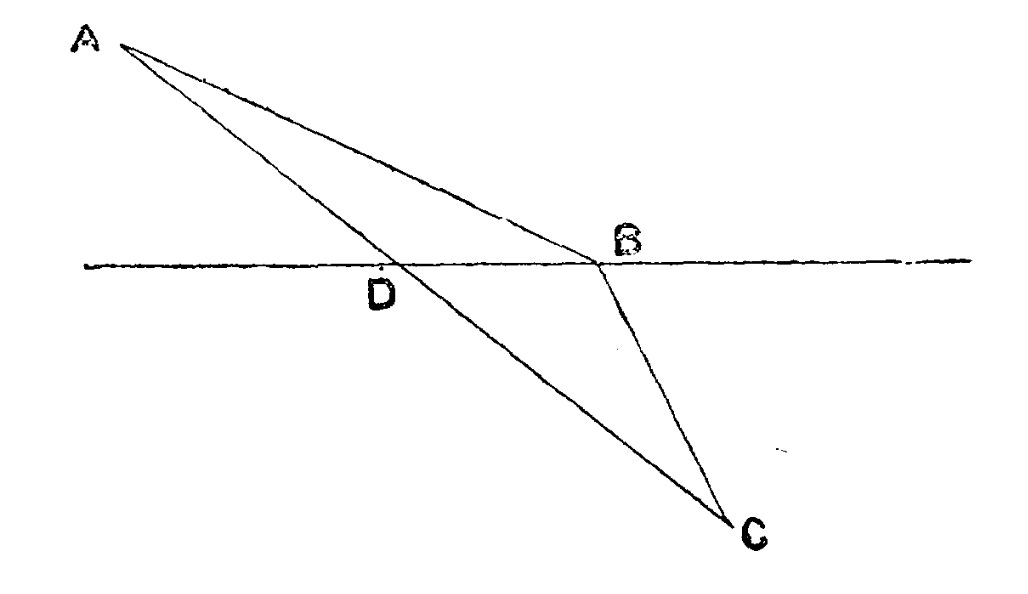

But it is necessary to move on and find the reason for refraction in our common principle, which is that nature always acts along the shortest and easiest paths. It seems at first that this could not succeed and that you yourself have made an objection which appears invincible. For, since on page 315 of your Book, the two lines CB,BA which contain the angle of incidence and that of refraction, are longer than the straight line ADC which forms the base of the triangle ABC, it follows that the ray from C to A, which traverses a shorter path than that of the two lines CB,BA, should, in accordance with our principle, be the sole and true route of nature, but which, nevertheless, is contrary to experience. But we can easily extricate ourselves from this difficulty by assuming, with you and with all those who have treated this matter, that the resistance of the media is different, and that there is always a certain ratio or proportion between those two resistances, when the two media have particular consistencies and are internally uniform. [Ross, p.74]

For example: if the resistance through medium A is double the resistance through medium C, then the resistance along CB will be to the resistance along BA, as CB is to double BA. And, if the resistance through medium C is double the resistance through medium A, then the resistance along CB will be to the resistance along BA, as CB is to half of BA. So, in these two cases, the two resistances along CB and BA, being combined, can be expressed as CB plus half of BA, or as CB plus twice BA. [Ross, p.76]

So it was Fermat who introduced the Principle of Least Time, in which light, passing from point A to point C, where A and C are in different media, passes through the point B on the intersection of the two media that ensures that the total time for AB,BC will be minimized.

Fermat’s principle of least time was picked up by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who wrote in his New Essays on Human Understanding, which was finished in 1704, but published posthumously, in 1765:

…the maxim that nature acts by the shortest way, or at least by the most determinate way, is sufficient by itself to explain almost the whole of optics, including the optics of reflection and refraction, i.e. the whole of what goes on ‘outside us’ in the actions of light. [Leibniz5, p.423]

The principle of least time is the precursor of the principle of least action, whose history is much more complicated and cannot be covered in a single post.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

Pierre de Fermat. The Battle for Light: Fermat vs. Descartes: A Sourcebook on Pierre de Fermat’s Principle of Least Time. A translation of the entire correspondence of Fermat on light, accompanied by texts he references, and including his complete writings on maxima and minima. Translated and edited by Jason Ross. 2024.

Paul Tannery et Charles Henry, éditeurs. Œuvres de Fermat. 4 volumes. Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils, 1891-1912.

Charles Adam & Paul Tannery, éditeurs. Œuvres de Descartes. 12 volumes. Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897-1910.

Christiaan Huygens. Treatise on Light. In which are explained the causes of that which occurs in Reflexion, & in Refraction. And particularly in the strange Refraction of Iceland Crystal. Rendered into English By Silvanus P. Thompson. New York: Dover, 1962. First published by Macmillan and Company, Limited, in 1912.

G.W. Leibniz. New Essays on Human Understanding. Translated and edited by Peter Remnant and Jonathan Bennett. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Seeing the history of these scientific debates is very cool. Thank you for this!

The principle of least action is one of the many consequences that can be deduced from taking the conservation of energy seriously. That it has been discovered and rediscovered by so many different paths is beautifully ironic.

Nice

I was hoping for the proof that AB-BC is shorter time.