One of the first things I did when I started my blog was to read, and write about, Galileo Galilei’s (1564-1642) book Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo [Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems—Ptolemaic and Copernican], published in May 1632. This is the book for which he was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life by the Holy Inquisition of the Roman Church. These posts can be found in my summary post My Writings on Galileo Galilei.

One thing I had not noted was that Galileo’s book was written as if there were, at the time, only two alternative theories: the geocentric (Earth-centered) Ptolemaic one, and the heliocentric (Sun-centered) Copernican one. But, there was at the time, in fact, a third alternative: geoheliocentrism, proposed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), in which the Sun revolves around the Earth and most of the planets revolve around the Sun.

During the seventeenth century, the Tychonian system was widely accepted and used by astronomers of the time, such as the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner (died 1650). And, approximately a century prior to Tycho, the Indian mathematician Keļallur Nīlakaṇṭha Somayāji (1444-1544) had also proposed essentially the same model.

Tycho’s system, which included an immobile Earth, has undergone development since he first proposed it. His disciple, Christen Sørensen Longomontanus (1562-1647), modified Tycho’s system by allowing the Earth to have a diurnal rotation. More recently, Simon Shack (https://www.tychos.space), while adopting the view of Tycho, has proposed additionally that the Earth does not remain in a fixed position, but slowly revolves in a small orbit taking approximately 25’000 years.

In today’s popular writings, geoheliocentrism is presented in a teleological manner, as a stepping stone towards geocentrism, a typical argument being that religion was the only reason that the Earth was placed at the center of the solar system. But Tycho gave clear technical arguments against the Copernican system that should be taken seriously. This is not exactly easy, as the vast majority of Tycho’s and Longomontanus’s writings are only available in Latin.

It is thus appropriate to consider geoheliocentrism as a completely separate system, worthy of examination. I therefore propose to write a series of posts on this subject.

This particular post, the first in the series, will focus on ancient Greece, and in particular on Heraclides Ponticus (c.390 BCE - c.310 BCE). I first read about him in Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers1. Koestler refers to the works of two historians of science and philosophy from the beginning of the 20th century: J.L.E. Dreyer2 and Pierre Duhem3.

Back in those days, Astronomy was not considered to be a part of Physics. Duhem writes:

Plato had formulated, in the most precise and general way, the problem of Astronomy, as it was understood until Kepler. It is necessary, he said, to take as hypotheses a certain number of circular and uniform motions, and these motions must be chosen in such a way that their composition safeguards the apparent course of the stars.4

So, in other words, the objective of Astronomy was not to explain the motion of the celestial bodies, but to provide geometrical models predicting their motion. This is known as “saving the appearances”.

Here is how Duhem introduces Heraclides:

Now, at the same time as Eudoxus and Aristotle, a bold innovator was rejecting the doctrine of the homocentric spheres and proposing new astronomical hypotheses, and these hypotheses formed the first outline of Copernicus’s system.

This innovator was Heraclides Ponticus. Born in Heraclea Pontica, Heraclides came to Athens as a young man to study philosophy; he had dealings with Plato and became one of his most illustrious disciples; according to Diogenes of Laërte, he also followed the lessons of Aristotle and those given by Speusippus, Plato's successor, at the Academy.

In his many writings, all of which have been lost, he was fond of upholding the most novel and least widely held opinions; this is why the Greeks gave him the nickname of Paradoxologist; as far as Astronomy was concerned, the Paradoxologist, as we shall see, was well served by his audacity.5

Notice here how Duhem has presented Heraclides as precursor of Copernicus, which, as we shall see, is not so clear.

Heraclides is well known for his supporting the idea of diurnal rotation of the Earth:

First of all, Heraclides must be ranked, without any possible dispute, among those who explained diurnal movement by keeping the sky of fixed stars immobile and by attributing to the Earth, around the axis of the World, a uniform rotation from west to east. There is an abundance of texts attributing this opinion to the Paradoxologist.6

Among those that Duhem quotes to support this point are Proclus (412-485) and Simplicius (480-540), respectively known for their commentaries on Plato and Aristotle. Here is Duhem quoting Simplicius:

Elsewhere, Simplicius is more explicit; he refers to authors, “such as Heraclides of Pontus and Aristarchus, who believe it possible to save appearances by keeping Heaven and the stars immobile and making the Earth turn from west to east around the poles of the equator, and that in such a way that every day it makes approximately one revolution (χινουμένης ἑχάστης ἡμέρας μίαν ἔγιστα περιστροφήν). They add the word approximately (ἔγγιστα)”, Simplicius continues, “because of the proper motion of the Sun, which is one degree per day”. Thus Heraclides, and Aristarchus after him, had recognised the need to distinguish the sidereal day from the solar day, and to attribute the former of these two durations to the rotation of the Earth.7

Now the next step taken by Heraclides was to recognize the revolution of Venus and Mercury around the Sun, while still supposing that the Sun revolves around the Earth. Duhem writes:

On the other hand, the strange motion of this planet, and the similar motion of Mercury, had attracted the attention of Plato; this philosopher had, on several occasions, pointed out the fact that Venus sometimes overtakes the Sun, sometimes allows itself to be overtaken by it, while maintaining an average speed exactly equal to that of the Sun.8

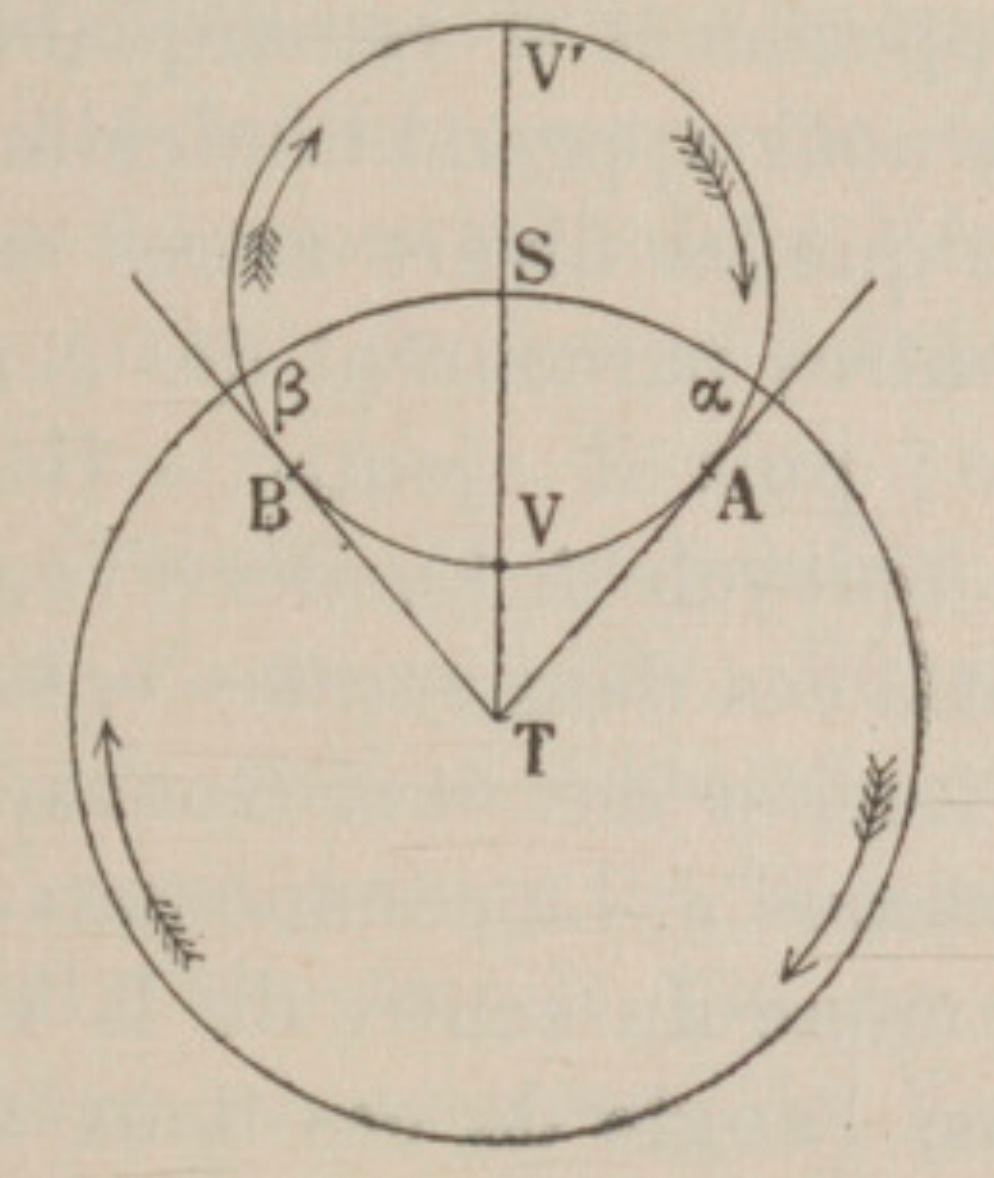

For his description of Heraclides’s thinking, Duhem uses the following diagram.

Heraclides discovered a way of saving these appearances by an ingenious and simple device. While the Sun S [in the figure] describes each year, from West to East, a circle of which the Earth T is the centre, let us imagine that Venus, while taking part in this movement, describes, in the same direction, a smaller circle AVBV′ of which the Sun is the centre; let us suppose, moreover, that this circle is described in a time equal to the duration of the synodic revolution of Venus, so well known to Eudoxus. All the phenomena that Venus presents to us will be explained in this way.

From point T, let us take two tangents, TA, TB, to the circle described by Venus; it is clear that we will never see Venus move away from the Sun, towards the East, by an angle greater than ATS nor, towards the West, by an angle greater than STB.

When Venus describes the AVB arc of its circle, the speed of this movement, projected onto the sphere of the fixed stars, will appear to be directed from east to west, in the opposite direction to the proper speed of the Sun; the projection of Venus on the sphere of the fixed stars will seem to move, on the zodiac, from west to east, with a speed equal to the difference between the two speeds we have just been talking about; it will seem to walk more slowly than the Sun; it will be joined by the projection of this star at the moment when the planet reaches point V of its circle, and then it will be overtaken by this projection.

On the contrary, while the planet Venus describes, on its circle, the arc BV′A, its projection seems to walk, on the ecliptic, from west to east, faster than the projection of the Sun; it joins the latter when the planet reaches point V′ of its circle, then it overtakes it.

This saves, at least qualitatively, the appearances, already well known to Plato, of the progress of Venus compared with that of the Sun.

The changes in the apparent size of Venus are also saved. Venus is further from the Earth than is the Sun while it describes on its circle the arc βV′α; it is nearer to us than the Sun while it traverses the arc αVβ.9

According to Duhem, the ideas of Heraclides, as presented up to here, were widely accepted through the centuries:

Reduced to the planets Mercury and Venus alone, the theory of Heraclides Ponticus found many supporters; it found them among the Greeks before Ptolemy and among the Latins after Ptolemy; it found them in the Middle Ages, among the Latin Scholastics who learned from the Platonists, Chalcidius, Macrobius and Martianus Cappella, at a time when Ptolemy and Aristotle were still unknown….10

In the following chapter, Duhem looks at the possibility that Heraclides was heliocentrist, i.e., a precursor of Copernicus. It all comes down to how to interpret a single-sentence passage in Greek, in which Germinus (1st century BCE) is quoted five centuries later by Simplicius. Here is the passage.

διὸ καὶ παρελθών τις φησὶν Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός, ὅτι καὶ κινουμένης πως τῆς γῆς, τοῦ δὲ ἡλίου μένοντός πως δύναται ἡ περὶ τὸν ἥλιον φαινομένη ἀνωμαλία σώζεσθαι. [Dreyer, p.132]

How to interpret this passage, in which the exact order of the words is not identical in different published editions, is not at all clear. There is a clear divergence between Duhem and J.L.E. Dreyer, each writing several pages thereon. Duhem, agreeing with the French mathematician Paul Tannery (1843-1904) and the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910), accepts it as evidence that Heraclides believed that the Earth revolved around the Sun. However, Dreyer, after a long discussion, writes as follows:

For if Herakleides had seriously believed that he had found the true explanation of the complicated motions of the planets, he would not have been afraid to publish his theory, judging by all we know of him. No doubt it is very tempting to assume that the motion of the earth, which was taught by Aristarchus in the following century, had already fifty or sixty years earlier been known to the man who had made the first step in the right direction by discovering the heliocentric motion of Mercury and Venus. But to build this assumption on a vague and probably corrupted passage, and on the supposition that παρὰ and περὶ are equivalent, or that παρὰ has been changed into περὶ, and to do this in the face not only of the absolute silence of all writers, but of the directly opposing testimony of Aëtius, seems too hazardous. [Dreyer, p.135, my emphasis]

It is well known that Aristarchus was a heliocentrist. Reading this passage from Dreyer, my impression is that it is quite possible that Heraclides was always a geoheliocentrist, and that 19th and 20th century scholars, convinced of the veracity of heliocentrism, “promoted” Heraclides and put him in the camp of the heliocentrists.

What is clear is that the idea, with which we associate Heraclides, that Mercury and Venus revolve around the Sun, and not around the Earth, was accepted in numerous circles throughout the centuries, and that supposing such did not necessarily imply accepting the idea of heliocentrism.

Several further posts will follow in this series.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

Arthur Koestler. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s changing vision of the Universe. With an Introduction by Herbert Butterfield. London: Arkara (Penguin Books), 1989. First published in 1959.

J.L.E. Dreyer. A History of Astronomy: from Thales to Kepler. Formerly titled History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler. Revised with a Foreword by W. H. Stahl. Second edition. New York: Dover, 1953. First published in 1905.

Pierre Duhem. Le Système du Monde. Histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic. Tome Premier. Paris: Librairie Scientifique A. Hermann et fils, 1913.

Platon avait formulé, de la manière la plus précise et la plus générale, le problème de l’Astronomie, tel qu’il a été compris jusqu’à Képler. Il faut, disait-il, prendre pour hypothèses un certain nombre de mouvements circulaires et uniformes, et ces mouvements, il les faut choisir de telle sorte que leur composition sauve le cours apparent des astres. [Duhem, p.399]

Or, à l’époque même d’Eudoxe et d’Aristote, un novateur audacieux, rejetant la doctrine des sphères homocentriques, proposait des hypothèses astronomiques nouvelles, et ces hypothèses dessinaient la première esquisse du système de Copernic.

Ce novateur était Héraclide du Pont. Né à Héraclée du Pont, Héraclide vint dès sa jeunesse à Athènes pour se livrer à l’étude de la Philosophie ; il eut commerce avec Platon et devint un de ses disciples les plus illustres ; selon Diogène de Laërte, il suivit également les leçons d'Aristote et celles qu’à l’Académie, donnait Speusippe, successeur de Platon.

Dans ses nombreux écrits, qui sont tous perdus, il aimait à soutenir les opinions les plus nouvelles et les moins répandues; aussi les Grecs lui avaient-ils donné le surnom de Paradoxologue ; en ce qui concerne les choses de l'Astronomie, le Paradoxologue, nous l’allons voir, fut bien servi par son audace. [Duhem, p.404]

Et d’abord, Héraclide doit être rangé, sans contestation possible, au nombre de ceux qui expliquaient le mouvement diurne en maintenant immobile le ciel des étoiles fixes et en attribuant à la Terre, autour de l’axe du Monde, une rotation uniforme d’occident en orient. Les textes abondent, qui mettent cette opinion au compte du Paradoxologue. [Duhem, p.405]

Ailleurs, Simplicius s’exprime d'une manière plus explicite ; il fait allusion aux auteurs, « tels qu’Héraclide du Pont et Aristarque, qui croient possible de sauver les apparences en maintenant immobiles le Ciel et les astres et en faisant tourner la Terre d’occident en orient autour des pôles de l'équateur, et cela de telle manière qu’elle fasse chaque jour à peu près un tour (χινουμένης ἑχάστης ἡμέρας μίαν ἔγγιστα περιστροφήν). Ils ajoutent le mot à peu près (ἔγγιστα) », poursuit Simplicius, « en raison du mouvement propre du Soleil, qui est d'un degré par jour ». Ainsi Héraclide, et Aristarque après lui, avaient reconnu la nécessité de distinguer le jour sidéral du jour solaire, et d’attribuer la première de ces deux durées à la rotation de la Terre. [Duhem, pp.405-406]

D’autre part, la marche étrange de cette planète, et la marche analogue de Mercure, avaient vivement sollicité et fortement retenu l’attention de Platon ; ce philosophe avait, à plusieurs reprises, signalé ce fait que Vénus tantôt dépasse le Soleil, tantôt se laisse dépasser par lui, tout en gardant une vitesse moyenne exactement égale à celle du Soleil. [Duhem, p.406]

Héraclide découvrit le moyen de sauver ces apparences par un artifice aussi simple qu’ingénieux. Tandis que le Soleil S (fig. 3) décrit chaque année, d’Occident en Orient, un cercle dont la Terre T est le centre, imaginons que Vénus, tout en prenant part à ce mouvement, décrive, dans le même sens, un cercle AVBV′ plus petit, dont le Soleil soit le centre ; supposons, en outre, que ce cercle soit décrit en un temps égal à la durée de révolution synodique de Vénus, si bien connue d’Eudoxe. Tous les phénomènes que Vénus nous présente seront ainsi expliqués.

Du point T, menons deux tangentes, TA, TB, au cercle décrit par Vénus ; il est clair que nous ne verrons jamais Vénus s’écarter du Soleil, vers l’Orient, d’un angle supérieur à ATS ni, vers l’Occident, d'un angle supérieur à STB.

Lorsque Vénus décrira l’arc AVB de son cercle, la vitesse de ce mouvement, projetée sur la sphère des étoiles fixes, semblera dirigée d’orient en occident, en sens contraire de la vitesse propre du Soleil ; la projection de Vénus sur la sphère des étoiles fixes semblera se mouvoir, sur le zodiaque, d’occident en orient, avec une vitesse égale à la différence des deux vitesses dont nous venons de parler ; elle semblera marcher moins vite que le Soleil ; elle sera rejointe par la projection de cet astre au moment où la planète parviendra au point V de son cercle, puis elle sera dépassée par cette projection.

Au contraire, tandis que la planète Vénus décrit, sur son cercle, l’arc BV′A, sa projection semble marcher, sur l’écliptique, de l’occident vers l'orient, plus vite que la projection du Soleil ; elle rejoint celle-ci lorsque la planète parvient au point V′ de son cercle, puis elle la dépasse.

Ainsi se trouvent sauvées, au moins d’une manière qualitative, les apparences, déjà bien connues de Platon, que présente la marche de Vénus comparée à celle du Soleil.

Les changements de grandeur apparente de Vénus sont également sauvés. Vénus est plus loin de la Terre que n’est le Soleil tandis qu’elle décrit sur son cercle l'arc βV′α ; elle est plus voisine de nous que le Soleil tandis qu’elle parcourt l'arc αVβ. [Duhem, pp.406-408]

Réduite aux seules planètes de Mercure et de Vénus, la théorie d’Héraclide du Pont a trouvé de nombreux partisans ; elle en a trouvé chez les Grecs avant Ptolémée et chez les Latins après Ptolémée ; elle en a trouvé au Moyen-Age, chez les Scolastiques latins qui s'instruisaient auprès des Platoniciens, de Chalcidius, de Macrobe, de Martianus Cappella, au temps où Ptolémée et Aristote étaient encore inconnus ; au moment où nous étudierons ce Néo-platonisme chrétien, nous rappellerons quelle fut, dans l’Antiquité, la fortune de cette théorie du Paradoxologue, et nous dirons quelle fut ensuite cette fortune jusqu’au temps de Copernic. [Duhem, p.410]

I’m sure you’re aware of Michael Flynn’s Great Ptolemaic Smackdown:

https://tofspot.blogspot.com/2013/08/the-great-ptolemaic-smackdown.html

Mr. Plaice,

It'd be wonderful to hear you address the divisive concept of a flat Earth. I happen to fall on the oblate spheroid side of the discussion, but am not an organized, formal, deep scholar as you and those whose works you plumb (and my brighter brothers) are.

Also, others' articles make reference to an Earth with an unevenly distributed, lumpy, "potato-shaped" gravitational field. Do you have any views or historical scholarship on that? (On an oblate tuber, or something?)

This site is riveting, even to one who understands maybe half of, it on a good day.

Thanks,

Al