This post is the last of a series of posts about William Gilbert’s De Magnete (On the Magnet1), which is composed of six books. This post is about Book Six. Here are the previous posts related to De Magnete.

De Magnete, Nothing Less than the First Ever Work of Experimental Physics

Book One, part 1: William Gilbert Writes about the Loadstone

Book One, part 2: William Gilbert Examines Iron, Calls Aristotle's Earth Element Dead

Book Two, part 1: William Gilbert Compares Electric Bodies to Magnetic Bodies

Book Two, part 2: William Gilbert Discusses Magnetic Bodies

Book Two, part 3: William Gilbert Considers the Internal Structure of the Terrella

Book Two, part 4: William Gilbert States that the Moon Causes the Tides

Book Two, part 5: William Gilbert Aligns Several Loadstones

Book Three, part 1: William Gilbert Explains How Magnetic Bodies Acquire Direction

Book Three, part 2: William Gilbert Shows the Direction of Compass Needles

Book Five, part 1: William Gilbert Calculates the Magnetic Dip

Book Five, part 2: William Gilbert Calls the Earth Animate

In this book, Gilbert moves on from experiments with the terrella to focus explicitly on the earth and to support the work of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), who had published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) in 1543.

HITHERTO we have spoken of the loadstone and magnetic bodies, how they conspire together and act on each other, and how they conform themselves to the terrella and to the earth. Now we have to treat of the globe of earth itself separately. [p.313]

For Gilbert, the key to the earth is its magnetic nature, from which he will argue that the earth’s revolution upon its axis and rotation about the sun are perfectly natural:

The dip of the magnetic needle (that wonderful turning of magnetic bodies to the body of the terrella by formal progression) is seen also in the earth most clearly. And that one experiment reveals plainly the grand magnetic nature of the earth, innate in all the parts thereof and diffused throughout. The magnetic energy, therefore, exists in the earth just as in the terrella, which is a part of the earth and homogenic in nature with it, but by art made spherical so it might correspond to the spherical body of the earth and be in agreement with the earth’s globe for the capital experiments. [p.314]

Gilbert argues that the motion of the earth was known to the ancients:

AMONG the ancients, Heraclides of Pontus, and Ecphantus, the Pythagoreans Nicetas of Syracuse and Aristarchus of Samos, and, as it seems, many others, held that the earth moves, that the stars set through the interposition of the earth, and that they rise through the earth’s giving way: they do give the earth motion, and the earth being, like a wheel, supported on its axis, rotates upon it from west to east. The Pythagorean Philolaus would have the earth to be one of the stars, and to turn in an oblique circle toward the fire, just as the sun and moon have their paths: Philolaus was an illustrious mathematician and a very experienced investigator of nature. [pp.317-318]

But, over time, there was a collapse of scientific understanding, and this knowledge was lost or dropped:

But when Philosophy had come to be handled by many, and had been given out to the public, then theories adapted to the capacity of the vulgar herd or supported with sophistical subtleties found entrance into the minds of the many, and, like a torrent, swept all before them, having gained favor with the multitude. Then were many fine discoveries of the ancients rejected and discredited — at the least were no longer studied and developed. [p.318]

It was only with the arrival of Copernicus that science began to be put on a proper footing:

First, therefore, Copernicus among moderns (a man most worthy of the praise of scholarship) undertook, with new hypotheses, to illustrate the phænomena of bodies in motion; and these demonstrations of reasons, other authors, men most conservent with all manner of learning, either follow, or, the more surely to discover the alleged (φαινομένην [phainomenen]) “symphony” of motion, do observe. Thus the suppositions and purely imaginary spheres postulated by Ptolemy and others for finding the times and periods of movements, are not of necessity to be accepted in the physical lectures of philosophers. [p.318]

Gilbert then launches an attack against the Ptolemaic system, and utters his utmost contempt for the concept of the primum mobile, the outer crystalline sphere of the universe in the Ptolemaic system, which supposedly carries the “fixed stars”:

But there cannot be diurnal motion of infinity or of an infinite body, nor, therefore, of this immeasurable primum mobile. The moon, neighbor of earth, makes her circuit in twenty-seven days; Mercury and Venus have a tardy movement; Mars completes his period in two years, Jupiter in twelve, Saturn in thirty. And the astronomers who ascribe motion to the fixed stars hold that it is completed, according to Ptolemy, in 36,000 years, or, according to Copernicus’s observations, in 25,816 years; thus in larger circles the motion and the completion of the course are ever more slow; and yet this primum mobile, surpassing all else in height and depth, immeasurable, has a diurnal revolution. Surely that is superstition, a philosophic fable, now believed only by simpletons and the unlearned; it is beneath derision; and yet in times past it was supported by calculation and comparison of movements, and was generally accepted by mathematicians, while the importunate rabble of philophasters [pseudothinkers] egged them on. [pp.321-322]

In language that resembles that of Galileo in the latter’s Dialogue, Gilbert writes that surely the motion of the earth is a lot more probable than this ridiculously high speed of the diurnal rotation of the primum mobile:

This seems to some philosophers wonderful and incredible, because of the ingrained belief that the mighty mass of the earth makes an orbital movement in twenty-four hours: it were more incredible that the moon should in the space of twenty-four hours traverse her orbit or complete her course; more incredible that the sun and Mars should do so; still more that Jupiter and Saturn; more than wonderful would be the velocity of the fixed stars and firmament; and let them imagine as best they may the wonders that confront them in the ninth sphere. But it is absurd to imagine a primum mobile, and, when imagined, to give to it a motion that is completed in twenty-four hours, denying that motion to the earth within the same space of time. For a great circle of earth, as compared to the circuit of the primum mobile is less than a stadium as compared to the whole earth. And if the rotation of the earth seems headlong and not to be permitted by nature because of its rapidity, then worse than insane, both as regards itself and the whole universe, is the motion of the primum mobile, as being in harmony or proportion with no other motion. [p.322]

In fact, Gilbert writes, the rotation of the earth, and of everything that accompanies it, does not meet any resistance:

For since it revolves in a space void of bodies, the incorporeal æther, all atmosphere, all emanations of land and water, all clouds and suspended meteors, rotate with the globe: the space above the earth’s exhalations is a vacuum; in passing through vacuum even the lightest bodies and those of least coherence are neither hindered nor broken up. Hence the entire terrestrial globe, with all its appurtenances, revolves placidly and meets no resistance. [p.326]

Gilbert concludes without a doubt that the diurnal revolution of the earth is a fact:

From these arguments, therefore, we infer, not with mere probability, but with certainty, the diurnal rotations of the earth; for nature ever acts with fewer rather than with many means; and because it is more accordant to reason that the one small body, the earth, should make a daily revolution than that the whole universe should be whirled around it. [p.327]

For Gilbert, the diurnal revolution of the earth is natural precisely because of the magnetic nature of the earth:

The day, therefore, which we call the natural day is the revolution of a meridian of the earth from sun to sun. And it makes a complete revolution from a fixed star to the same fixed star again. Bodies that by nature move with a motion circular, equable, and constant, have in their different parts various metes and bounds. Now the earth is not a chaos nor a chance medley mass, but through its astral property has limits agreeable to the circular motion, to wit, poles that are not merely mathematical expressions, an equator that is not a mere fiction, meridians, too, and parallels; and all these we find in the earth, permanent, fixed, and natural; they are demonstrated with many experiments in the magnetic philosophy. For in the earth are poles set at fixed points, and at these poles the verticity from both sides of the plane of the equator is manifested with greatest force through the co-operation of the whole; and with these poles the diurnal rotation coincides. [p.328, emphasis mine]

On the other hand, the firmament, or sky, or outer space as we would call it today, does not have any natural poles forming an axis around which to revolve:

But no revolutions of bodies, no movements of planets, show any sensible, natural poles in the firmament or in any primum mobile; neither does any argument prove their existence; they are the product of imagination. We, therefore, having directed our inquiry toward a cause that is manifest, sensible, and comprehended by all men, do know that the earth rotates on its own poles, proved by many magnetical demonstrations to exist. For not in virtue only of its stability and its fixed permanent position does the earth possess poles and verticity; it might have had another direction, as eastward or westward, or toward any other quarter. [p.328]

Gilbert also argues that the earth is well suited for circular motion, as its parts revolve with it:

For all planets have a like movement to the east, in accordance with the succession of the zodiacal signs, whether it be Mercury or Venus within the sun’s orbit, or whether they revolve round the sun. That the earth is fitted for circular movement is proved by its parts, which, when separated from the whole, do not simply travel in a right line, as the Peripatetics taught, but rotate also. [pp.330-331]

He also uses a kind of teleological argument, stating that were the earth not to move, it would be lifeless:

Now generation results from motion, and without motion all nature would be torpid. The sun’s motions, the moon’s motions, produce changes; the earth’s motion awakens the inner life of the globe; animals themselves live not without motion and incessant working of the heart and the arteries. As for the single motion in a right line to the centre, that this is the only movement in the earth, and that the movement of an individual body is one and single, — the arguments for it have no weight, for that motion in a right line is but the inclination toward their origin, not only of the earth, but also of the parts of the sun, the moon, and all the other globes; but these move in a circle also. Joannes Costeus, who is in doubt as to the cause of the earth’s motion, regards the magnetic energy to be intrinsic, active, and controlling; the sun he holds to be an extrinsic promovent cause; nor is the earth so mean and vile a body as it is commonly reputed to be. Hence, according to him, the diurnal motion is produced by the earth, for the earth’s sake and for the earth’s behoof. [p.338]

He continues with this teleological approach, arguing that the fact that the earth’s axis is on a tilt with respect to the ecliptic, also encourages life on earth:

HAVING shown the nature and causes of the earth’s diurnal revolution, produced partly by the energy of the magnetic property and partly by the superiority of the sun and his light, we have now to treat of the distance of the earth’s poles from those of the ecliptic — a condition very necessary for man’s welfare. For if the poles of the world or the earth were fixed at the poles of the zodiac, then the equator would lie exactly under the line of the ecliptic, and there would be no change of seasons, — neither winter, nor summer, nor spring, nor fall, — but the face of things would persist forever unchanging. Hence (for the everlasting good of man) the earth’s axis declined from the pole of the zodiac just enough to suffice for generation and diversification. [p.347]

After dealing with the earth’s diurnal revolution and the annual rotation around the sun, Gilbert focuses on the last technical issue in De Magnete, namely the precession of the equinoxes:

Around these poles of the ecliptic the bearing of the earth’s poles rotates, and because of this motion we have the precession of the equinoxes. [p.348]

He begins by explaining that Hipparchus of Rhodes was the first to notice that there is a difference between the equinoctial or solstitial year — the number of days between successive equinoxes or solstices — and the sidereal year — the number of days between a specific fixed star reappearing in the same part of the sky:

THE early astronomers, not noting the inequality of years, made no distinction between the equinoctial or solstitial revolving year and the [sidereal] year determined from a fixed star. They also deemed the Olympian years, which were reckoned from the rising of the Dog Star or Sirius (Canicula) to be the same as those reckoned from the solstice. Hipparchus the Rhodian was the first to notice that there is a difference between the two, and found another year, calculated from fixed stars, of greater length than the equinoctial or solstitial: hence he supposed that the stars too have a consequent motion, though a very slow one, nor readily noticeable. [p.348]

For Gilbert, it is precisely the motion of the earth that explains this difference:

But we will prove that this motion proceeds from a certain revolution of the earth’s axis, and that the eighth sphere, so called, the firmament, or aplanes, with its ornament of innumerable globes and stars (the distances of which from earth have never been by any man demonstrated, nor ever can be), does not revolve. [p.349]

Once again, Gilbert returns to using a teleological argument:

For by this motion the rising and setting of stars in all horizons are changed, as also their culminations in the zenith, so that stars that once were vertical are now some degrees distant from the zenith. Provision has been made by nature for the earth’s soul or its magnetic energy — just as in attempering, receiving, and diverting the sun’s rays and light in fitting seasons, it was necessary that the bearings of the earth’s pole should be 23 degrees and more distant from the poles of the ecliptic; so that now in regulating and in receiving in due order and succession the luminous rays of the fixed stars, the earth’s poles should revolve at the same distance from the ecliptic in the arctic circle of the ecliptic, or rather that they should creep with slow gait, because the actions of the stars do not always persist in the same parallel circles, but have a slower change; for the influences of the stars are not so powerful that the desired course should be more rapid. [p.350]

The precession of the equinoxes has, according to Gilbert, long-term effects on the seasons, on life, and on human culture and history:

Thus do all the stars change their light rays at the earth’s surface, because of this admirable magnetic inflection of the earth’s axis. Hence the ever new changes of the seasons; hence are regions more or less fruitful, more or less sterile; hence changes in the character and the manners of nations, in governments and in laws, according to the power of the fixed stars, the strength thence derived or lost, and according to the individual and specific nature of the fixed stars as they culminate; or the effects may be due to their risings and settings or to new conjunctions in the meridian. [pp.350-351]

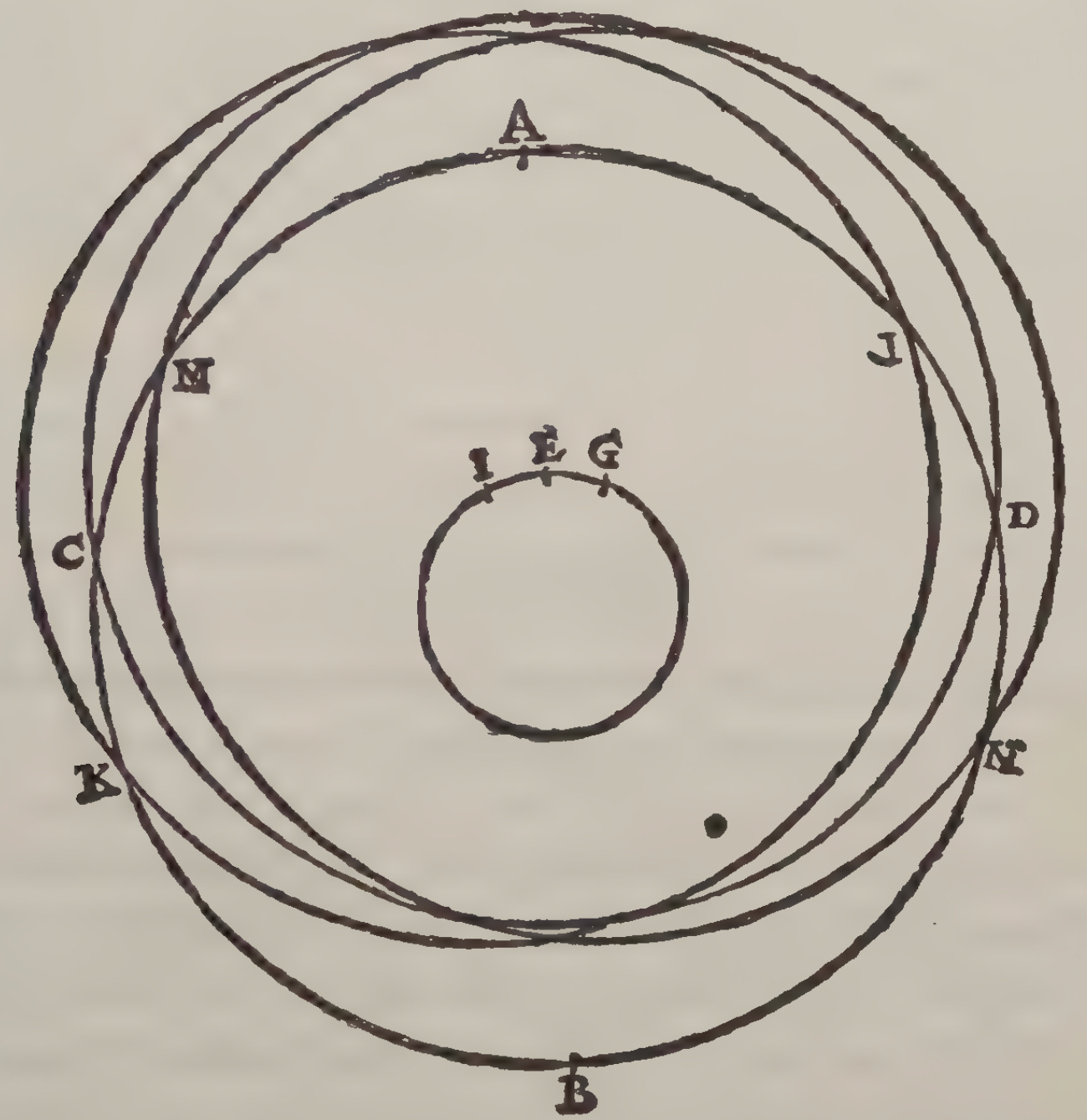

Gilbert illustrates the precession of the equinoxes with the following diagram:

The precession of the equinoxes from the equal motion of the earth’s pole in the zodiacal circle is here demonstrated, Let ABCD be the ecliptic; IEG the Arctic zodiacal circle. Now if the earth’s pole looks toward E, then the equinoxes are at D, C. Suppose this to be in the time of Metho, when the horns of Aries were in the equinoctial colure. But if the earth’s pole has advanced to I, then K, L will be the equinoxes, and stars in the ecliptic C will seem to have moved forward over the whole arc KC, following the signs; L advances by precession over the arc DL, counter to the order of the signs; but the opposite would be the case if the point G were to regard the earth’s poles, and the motion be from E toward G; for then M, N would be the equinoxes, and the fixed stars would anticipate at C and D, counter to the order of the signs. [pp.351-352]

It turns out that, like for declination and inclination, there is variation in the precession of the equinoxes:

THE change in the equinoxes is not always equal, but becomes sometimes more rapid, sometimes more slow; for the earth’s poles travel unequally in the Arctic and in the Antarctic zodiacal circle, and recede from the middle line on both sides; hence the obliquity of the zodiac seems to change to the equator (ad æquatorem immutari). And when this became known through protracted observations, it was apparent that the true equinoctial points were elongated from the mean equinoctial points 70 minutes to one side or the other in the greatest prostaphæresi; while the solstices either approach the equator equally by 12 minutes or recede to the same extent; so that the nearest approach is 23 deg. 28 min. and the greatest elongation 23 deg. 52 min. [pp.352-353]

The technical issues of the revolution of the earth about its axis, the rotation of the earth about the sun, and the precession of the equinoxes having been dealt with, Gilbert returns to the fact that most of the savants of his day are willing to invent and perpetuate the most absurd concepts, while refusing the most obvious explanation: Eppur se muove [And yet it moves].

Now though we see in all this how loath these mathematicians are to ascribe any motion to the earth, which is a very small body, nevertheless they drive and whirl the heavens, which are vast and immense beyond human comprehension and human imagination: they construct three heavens, postulate three inconceivable monstrosities, to account for a few unexplained motions. [p.354]

For Gilbert, it was Copernicus who discovered the anomaly of the precession of equinoxes. And further anomalies remain to be discovered:

At last Copernicus, through his own observations and those of Timochares, Aristarchus the Samian, Menelaus, Ptolemy, Machometes Aracensis and Alphonsus, discovered the anomalies of the motion of the earth’s axis; though I have no doubt that other anomalies also will appear some centuries hence, for it is difficult, save in periods of many ages, to note so slow a movement, wherefore we still are ignorant of the mind of nature, what she is aiming at through this inequality of motion. [p.354]

However, more data is needed to find exact physical causes, and to make exact predictions:

Thus do the moderns, and in particular Copernicus, restorer of astronomy, describe the variations of the movement of the earth’s axis, so far as the same is made possible by the observations of the ancients down to our day; but we still lack many and more exact observations to fix anything positively as to the anomaly of the movement of the precessions, as also of the obliquity of the zodiac. For since the time when in various observations this anomaly was first noted, only one half of a period of obliquity has passed. Hence all these points touching the unequal movement of precession and obliquity are undecided and undefined, and so we cannot assign with certainty any natural causes for the motion. [p.358]

In this manner, Book Six of De Magnete concludes. For Gilbert, the Copernican model was not just a mathematical invention, but a reflection of reality. Gilbert took up the gauntlet, and openly supported Copernicus, despite the fact that in Protestant circles his model was widely disputed, and that very year, in 1600, in Rome, Giordano Bruno had been burnt for heresy, including for supporting Copernicus.

It will be natural for some of my next posts to focus on Bruno and Copernicus.

If you wish to donate to support my work, please use the Buy Me a Coffee app.

William Gilbert. De Magnete. Dover, New York, 1958. Translation by P. Fleury Mottelay of De Magnete, first published in 1600.

Impressive that Hipparchus of Rhodes and Copernicus noticed the precession of the equinoxes. That requires detailed record keeping. I wonder how Gilbert learned about Hipparchus.

Newton's law of gravity predicts the paths of planets, yet it does not explain why all planets move in the same plane and the same direction. That planets orbit the sun is unbelievably unlikely. An orbit only works for exact distances and weights. Looking forward to read about the role magnetism and electricity might play in that!